1798 1st American ed Napoleon Bonaparte in ITALY French

Similar Sale History

View More Items in Books, Magazines & Papers

Related Books, Magazines & Papers

More Items in Books, Magazines & Papers

View MoreRecommended Collectibles

View More

Item Details

Description

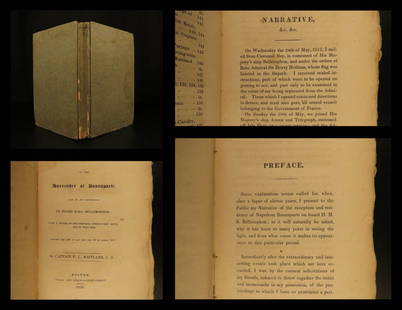

1798 1st American ed Napoleon Bonaparte in ITALY French Revolution War Campaigns

Napoléon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821) was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars. As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814, and again in 1815.

Item number: #6229

Price: $450

Main author: François ReneÌ Jean Pommereul, baron de; John Davis (transl.)

Title: Campaign of General Buonaparte in Italy, during the fourth and fifth years of the French republic.

Published: New-York : Printed [by Thomas Greenleaf for Henry Caritat] at the Argus Office., M, DCC, XCVIII. [1798]

Language: English

Notes & contents:

1st American edition – very rare!

Famous documentary study of Napoleon in Italy

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure leather binding

Pages: complete with all 304 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: New-York : Printed [by Thomas Greenleaf for Henry Caritat] at the Argus Office., M, DCC, XCVIII. [1798]

Size: ~8.5in X 5in (22cm x 13cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our first priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$450

Napoléon Bonaparte (/nəˈpoÊŠliÉ™n, -ˈpoÊŠljÉ™n/;[2] French: [napÉ”leɔ̃ bÉ”napaÊt], born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821) was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars. As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814, and again in 1815. Napoleon dominated European affairs for over a decade while leading France against a series of coalitions in the Napoleonic Wars. He won most of these wars and the vast majority of his battles, rapidly gaining control of continental Europe before his ultimate defeat in 1815. One of the greatest commanders in history, his campaigns are studied at military schools worldwide and he remains one of the most celebrated and controversial political figures in Western history.[3][4] In civil affairs, Napoleon had a major long-term impact by bringing liberal reforms to the territories that he conquered, especially the Low Countries, Switzerland, and large parts of modern Italy and Germany. He implemented fundamental liberal policies in France and throughout Western Europe.[note 1] His lasting legal achievement, the Napoleonic Code, has been adopted in various forms by a quarter of the worlds legal systems, from Japan to Quebec.[10][11][12]

Napoleon was born in Corsica to a relatively modest family of noble Tuscan ancestry. Serving in the French army, Napoleon supported the Revolution from the outset in 1789 and tried to spread its ideals to Corsica, but was banished from the island in 1793. Two years later, he saved the French government from collapse by firing on the Parisian mobs with cannons. After the Directory rewarded Napoleon by giving him command of the Army of Italy at age 26, he began his first military campaign against the Austrians and their Italian allies, scoring a series of decisive victories that made him famous all across Europe. He followed the defeat of the Allies in Europe by commanding a military expedition to Egypt in 1798, conquering the Ottoman province after defeating the Mamelukes and launching modern Egyptology through the discoveries made by his army.

After returning from Egypt, Napoleon engineered a coup in November 1799 and became First Consul of the Republic. With the Concordat of 1801, Napoleon restored the religious powers of the Catholic Church but kept the lands seized by the Revolution. The state nominated the bishops and controlled church finances. He extended his political control over France until the Senate declared him Emperor of the French in 1804, launching the French Empire. Intractable differences with the British meant that the French were facing a Third Coalition by 1805. Napoleon shattered this coalition with decisive victories in the Ulm Campaign and a historic triumph at the Battle of Austerlitz, which led to the elimination of the Holy Roman Empire. In October 1805, however, a Franco-Spanish fleet was destroyed at the Battle of Trafalgar, allowing Britain to impose a naval blockade of the French coasts. In retaliation, Napoleon established the Continental System in 1806 to cut off European trade with Britain. The Fourth Coalition took up arms against him the same year because Prussia became worried about growing French influence on the continent. After quickly knocking out Prussia at the battles of Jena and Auerstedt, Napoleon turned his attention towards the Russians and annihilated them in 1807 at Friedland, which forced the Russians to accept the Treaties of Tilsit.

Hoping to extend the Continental System, Napoleon invaded Iberia and declared his brother Joseph the King of Spain in 1808. The Spanish and the Portuguese revolted with British support. The Peninsular War, noted for its brutal guerrilla warfare, lasted six years and culminated in an Allied victory. Fighting also erupted in Central Europe, as the Austrians launched another attack against the French in 1809. Napoleon defeated them at the Battle of Wagram, dissolving the Fifth Coalition formed against France. By 1811, Napoleon ruled over 70 million people across an empire that had domination in Europe, which had not witnessed this level of political consolidation since the days of the Roman Empire.[13] He maintained his strategic status through a series of alliances and family appointments. He created a new aristocracy in France while allowing the return of nobles who had been forced into exile by the Revolution.

Tensions over rising Polish nationalism and the economic effects of the Continental System led to renewed confrontation with Russia. To enforce his blockade, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia in 1812 that ended in catastrophic failure for the French. In 1813, Prussia and Austria joined Russian forces in a Sixth Coalition against France. A chaotic military campaign eventually culminated in a large Allied army defeating Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig in October. The next year, the Allies invaded France and captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April 1814. He was exiled to the island of Elba. The Bourbons were restored to power and the French lost most of the territories that they had conquered since the Revolution. However, Napoleon escaped from Elba in February 1815 and took control of the government once again. The Allies formed a Seventh Coalition, which ultimately defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in June. He was then captured by the British and imprisoned on the remote island of Saint Helena. His death in 1821 at the age of 51 was received by shock and grief throughout Europe. In 1840, a million people witnessed his remains returning to Paris, where they still reside at Les Invalides.[14]

Contents [hide]

1Origins and education

2Early career

2.1Siege of Toulon

2.213 Vendémiaire

2.3First Italian campaign

2.4Egyptian expedition

3Ruler of France

3.1French Consulate

3.1.1Temporary peace in Europe

3.2French Empire

3.2.1War of the Third Coalition

3.2.2Middle-Eastern alliances

3.2.3War of the Fourth Coalition and Tilsit

3.2.4Peninsular War and Erfurt

3.2.5War of the Fifth Coalition and Marie Louise

3.2.6Invasion of Russia

3.2.7War of the Sixth Coalition

3.2.8Exile to Elba

3.2.9Hundred Days

4Exile on Saint Helena

4.1Death

4.1.1Cause of death

5Religions

5.1Concordat

5.2Religious emancipation

6Personality

7Image

8Reforms

8.1Napoleonic Code

8.2Warfare

8.3Metric system

8.4Education

9Memory and evaluation

9.1Criticism

9.2Propaganda and memory

9.3Long-term impact outside France

10Marriages and children

11Titles, styles, honours, and arms

12Ancestry

13Notes

14Citations

15References

15.1Biographical studies

15.2Specialty studies

15.3Historiography and memory

16External links

Origins and education

Half-length portrait of a wigged middle-aged man with a well-to-do jacket. His left hand is tucked inside his waistcoat.

Napoleons father Carlo Buonaparte was Corsicas representative to the court of Louis XVI of France.

Napoleon was born on 15 August 1769, to Carlo Maria di Buonaparte and Maria Letizia Ramolino, in his familys ancestral home Casa Buonaparte in Ajaccio, the capital of the island of Corsica. He was their fourth child and third son. This was a year after the island was transferred to France by the Republic of Genoa.[15] He was christened Napoleone di Buonaparte, probably named after an uncle (an older brother who did not survive infancy was the first of the sons to be called Napoleone). In his 20s, he adopted the more French-sounding Napoléon Bonaparte.[16][note 2]

The Corsican Buonapartes were descended from minor Italian nobility of Tuscan origin, who had come to Corsica from Liguria in the 16th century.[17][18]

Head and shoulders portrait of a white-haired, portly, middle-aged man with a pinkish complexion, blue velvet coat, and a ruffle

The nationalist Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli; portrait by Richard Cosway, 1798

His father Nobile Carlo Buonaparte was an attorney, and was named Corsicas representative to the court of Louis XVI in 1777. The dominant influence of Napoleons childhood was his mother, Letizia Ramolino, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child.[19] Napoleons maternal grandmother had married into the Swiss Fesch family in her second marriage, and Napoleons uncle, the later cardinal Joseph Fesch, would fulfill the role as protector of the Bonaparte family for some years.

He had an elder brother Joseph, and younger siblings: Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline, and Jérôme. A boy and girl were born before Joseph but died in infancy. Napoleon was baptised as a Catholic.[20]

Napoleons noble, moderately affluent background afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time.[21] In January 1779, he was enrolled at a religious school in Autun. In May, he was admitted to a military academy at Brienne-le-Château.[22] His mother language was Corsican, and he always spoke French with a marked Corsican accent and never learned to spell French properly.[23] He was teased by other students for his accent and applied himself to reading.[24] An examiner observed that Napoleon has always been distinguished for his application in mathematics. He is fairly well acquainted with history and geography... This boy would make an excellent sailor.[25][note 3]

On completion of his studies at Brienne in 1784, Napoleon was admitted to the elite École Militaire in Paris. He trained to become an artillery officer and, when his fathers death reduced his income, was forced to complete the two-year course in one year.[27] He was the first Corsican to graduate from the École Militaire.[27] He was examined by the famed scientist Pierre-Simon Laplace.[28]

Early career

Napoleon Bonaparte, aged 23, Lieutenant-Colonel of a battalion of Corsican Republican volunteers

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment.[22][note 4] He served in Valence and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, and took nearly two years leave in Corsica and Paris during this period. He was a fervent Corsican nationalist, and wrote to Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli in May 1789, As the nation was perishing I was born. Thirty thousand Frenchmen were vomited on to our shores, drowning the throne of liberty in waves of blood. Such was the odious sight which was the first to strike me.[30]

He spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. He supported the Jacobin faction and gained command over a battalion of volunteers. He was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792, despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against a French army in Corsica.[31]

He returned to Corsica and came into conflict with Paoli, who had decided to split with France and sabotage the French assault on the Sardinian island of La Maddalena.[32] Bonaparte and his family fled to the French mainland in June 1793 because of the split with Paoli.[33]

Siege of Toulon

Main article: Siege of Toulon

Bonaparte at the Siege of Toulon

In July 1793, Bonaparte published a pro-republican pamphlet entitled Le souper de Beaucaire (Supper at Beaucaire) which gained him the support of Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of the Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. With the help of his fellow Corsican Antoine Christophe Saliceti, Bonaparte was appointed artillery commander of the republican forces at the siege of Toulon.[34]

He adopted a plan to capture a hill where republican guns could dominate the citys harbour and force the British to evacuate. The assault on the position led to the capture of the city, but during it Bonaparte was wounded in the thigh. He was promoted to brigadier general at the age of 24. Catching the attention of the Committee of Public Safety, he was put in charge of the artillery of Frances Army of Italy.[35]

Napoleon spent time as inspector of coastal fortifications on the Mediterranean coast near Marseille while he was waiting for confirmation of the Army of Italy post. He devised plans for attacking the Kingdom of Sardinia as part of Frances campaign against the First Coalition.[36] Augustin Robespierre and Saliceti were ready to listen to the freshly promoted artillery general.[37]

The French army carried out Bonapartes plan in the Battle of Saorgio in April 1794, and then advanced to seize Ormea in the mountains. From Ormea, they thrust west to outflank the Austro-Sardinian positions around Saorge. Later, Augustin Robespierre sent Bonaparte on a mission to the Republic of Genoa to determine that countrys intentions towards France.[36]

13 Vendémiaire

Main article: 13 Vendémiaire

Some contemporaries alleged that Bonaparte was put under house arrest at Nice for his association with the Robespierres following their fall in the Thermidorian Reaction in July 1794, but Napoleons secretary Bourrienne disputed the allegation in his memoirs. According to Bourrienne, jealousy was responsible, between the Army of the Alps and the Army of Italy (with whom Napoleon was seconded at the time).[38] Bonaparte dispatched an impassioned defense in a letter to representants Salicetti and Albitte, and subsequently he was acquitted of any wrongdoing.[39]

He was released within two weeks and, due to his technical skills, was asked to draw up plans to attack Italian positions in the context of Frances war with Austria. He also took part in an expedition to take back Corsica from the British, but the French were repulsed by the Royal Navy.[40]

By 1795, Bonaparte had become engaged to Désirée Clary, daughter of François Clary. Désirées sister Julie Clary had married Bonapartes elder brother Joseph.[41] In April 1795, he was assigned to the Army of the West, which was engaged in the War in the Vendée—a civil war and royalist counter-revolution in Vendée, a region in west central France on the Atlantic Ocean. As an infantry command, it was a demotion from artillery general—for which the army already had a full quota—and he pleaded poor health to avoid the posting.[42]

Etching of a street, there are a lot pockets of smoke due to a group of republican artillery firing on royalists across the street at the entrance to a building

Journée du 13 Vendémiaire. Artillery fire in front of the Church of Saint-Roch, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré

He was moved to the Bureau of Topography of the Committee of Public Safety and sought unsuccessfully to be transferred to Constantinople in order to offer his services to the Sultan.[43] During this period, he wrote the romantic novella Clisson et Eugénie, about a soldier and his lover, in a clear parallel to Bonapartes own relationship with Désirée.[44] On 15 September, Bonaparte was removed from the list of generals in regular service for his refusal to serve in the Vendée campaign. He faced a difficult financial situation and reduced career prospects.[45]

On 3 October, royalists in Paris declared a rebellion against the National Convention.[46] Paul Barras, a leader of the Thermidorian Reaction, knew of Bonapartes military exploits at Toulon and gave him command of the improvised forces in defence of the Convention in the Tuileries Palace. Napoleon had seen the massacre of the Kings Swiss Guard there three years earlier and realised that artillery would be the key to its defence.[22]

He ordered a young cavalry officer named Joachim Murat to seize large cannons and used them to repel the attackers on 5 October 1795—13 Vendémiaire An IV in the French Republican Calendar. 1,400 royalists died and the rest fled.[46] He had cleared the streets with a whiff of grapeshot, according to 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History.[47][48]

The defeat of the royalist insurrection extinguished the threat to the Convention and earned Bonaparte sudden fame, wealth, and the patronage of the new government, the Directory. Murat married one of Napoleons sisters and became his brother-in-law; he also served under Napoleon as one of his generals. Bonaparte was promoted to Commander of the Interior and given command of the Army of Italy.[33]

Within weeks, he was romantically attached to Joséphine de Beauharnais, the former mistress of Barras. The couple married on 9 March 1796 in a civil ceremony.[49]

First Italian campaign

Main article: Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars

A three-quarter-length depiction of Bonaparte, with black tunic and leather gloves, holding a standard and sword, turning backwards to look at his troops

Bonaparte at the Pont dArcole, by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, (ca. 1801), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Two days after the marriage, Bonaparte left Paris to take command of the Army of Italy. He immediately went on the offensive, hoping to defeat the forces of Piedmont before their Austrian allies could intervene. In a series of rapid victories during the Montenotte Campaign, he knocked Piedmont out of the war in two weeks. The French then focused on the Austrians for the remainder of the war, the highlight of which became the protracted struggle for Mantua. The Austrians launched a series of offensives against the French to break the siege, but Napoleon defeated every relief effort, scoring notable victories at the battles of Castiglione, Bassano, Arcole, and Rivoli. The decisive French triumph at Rivoli in January 1797 led to the collapse of the Austrian position in Italy. At Rivoli, the Austrians lost up to 14,000 men while the French lost about 5,000.[50]

The next phase of the campaign featured the French invasion of the Habsburg heartlands. French forces in Southern Germany had been defeated by the Archduke Charles in 1796, but the Archduke withdrew his forces to protect Vienna after learning about Napoleons assault. In the first notable encounter between the two commanders, Napoleon pushed back his opponent and advanced deep into Austrian territory after winning at the Battle of Tarvis in March 1797. The Austrians were alarmed by the French thrust that reached all the way to Leoben, about 100 km from Vienna, and finally decided to sue for peace.[51] The Treaty of Leoben, followed by the more comprehensive Treaty of Campo Formio, gave France control of most of northern Italy and the Low Countries, and a secret clause promised the Republic of Venice to Austria. Bonaparte marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending 1,100 years of independence. He also authorized the French to loot treasures such as the Horses of Saint Mark.[52]

His application of conventional military ideas to real-world situations enabled his military triumphs, such as creative use of artillery as a mobile force to support his infantry. He remarked later in life: I have fought sixty battles and I have learned nothing which I did not know at the beginning. Look at Caesar; he fought the first like the last.[53]

Bonaparte could win battles by concealment of troop deployments and concentration of his forces on the hinge of an enemys weakened front. If he could not use his favourite envelopment strategy, he would take up the central position and attack two co-operating forces at their hinge, swing round to fight one until it fled, then turn to face the other.[54] In this Italian campaign, Bonapartes army captured 150,000 prisoners, 540 cannons, and 170 standards.[55] The French army fought 67 actions and won 18 pitched battles through superior artillery technology and Bonapartes tactics.[56]

During the campaign, Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics. He founded two newspapers: one for the troops in his army and another for circulation in France.[57] The royalists attacked Bonaparte for looting Italy and warned that he might become a dictator.[58] All told, Napoleons forces extracted an estimated $45 million in funds from Italy during their campaign there, another $12 million in precious metals and jewels; atop that, his forces confiscated more than three-hundred priceless paintings and sculptures.[59] Bonaparte sent General Pierre Augereau to Paris to lead a coup détat and purge the royalists on 4 September—Coup of 18 Fructidor. This left Barras and his Republican allies in control again but dependent on Bonaparte, who proceeded to peace negotiations with Austria. These negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Bonaparte returned to Paris in December as a hero.[60] He met Talleyrand, Frances new Foreign Minister—who later served in the same capacity for Emperor Napoleon—and they began to prepare for an invasion of Britain.

6229

Napoléon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821) was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars. As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814, and again in 1815.

Item number: #6229

Price: $450

Main author: François ReneÌ Jean Pommereul, baron de; John Davis (transl.)

Title: Campaign of General Buonaparte in Italy, during the fourth and fifth years of the French republic.

Published: New-York : Printed [by Thomas Greenleaf for Henry Caritat] at the Argus Office., M, DCC, XCVIII. [1798]

Language: English

Notes & contents:

1st American edition – very rare!

Famous documentary study of Napoleon in Italy

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure leather binding

Pages: complete with all 304 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: New-York : Printed [by Thomas Greenleaf for Henry Caritat] at the Argus Office., M, DCC, XCVIII. [1798]

Size: ~8.5in X 5in (22cm x 13cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our first priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$450

Napoléon Bonaparte (/nəˈpoÊŠliÉ™n, -ˈpoÊŠljÉ™n/;[2] French: [napÉ”leɔ̃ bÉ”napaÊt], born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821) was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars. As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814, and again in 1815. Napoleon dominated European affairs for over a decade while leading France against a series of coalitions in the Napoleonic Wars. He won most of these wars and the vast majority of his battles, rapidly gaining control of continental Europe before his ultimate defeat in 1815. One of the greatest commanders in history, his campaigns are studied at military schools worldwide and he remains one of the most celebrated and controversial political figures in Western history.[3][4] In civil affairs, Napoleon had a major long-term impact by bringing liberal reforms to the territories that he conquered, especially the Low Countries, Switzerland, and large parts of modern Italy and Germany. He implemented fundamental liberal policies in France and throughout Western Europe.[note 1] His lasting legal achievement, the Napoleonic Code, has been adopted in various forms by a quarter of the worlds legal systems, from Japan to Quebec.[10][11][12]

Napoleon was born in Corsica to a relatively modest family of noble Tuscan ancestry. Serving in the French army, Napoleon supported the Revolution from the outset in 1789 and tried to spread its ideals to Corsica, but was banished from the island in 1793. Two years later, he saved the French government from collapse by firing on the Parisian mobs with cannons. After the Directory rewarded Napoleon by giving him command of the Army of Italy at age 26, he began his first military campaign against the Austrians and their Italian allies, scoring a series of decisive victories that made him famous all across Europe. He followed the defeat of the Allies in Europe by commanding a military expedition to Egypt in 1798, conquering the Ottoman province after defeating the Mamelukes and launching modern Egyptology through the discoveries made by his army.

After returning from Egypt, Napoleon engineered a coup in November 1799 and became First Consul of the Republic. With the Concordat of 1801, Napoleon restored the religious powers of the Catholic Church but kept the lands seized by the Revolution. The state nominated the bishops and controlled church finances. He extended his political control over France until the Senate declared him Emperor of the French in 1804, launching the French Empire. Intractable differences with the British meant that the French were facing a Third Coalition by 1805. Napoleon shattered this coalition with decisive victories in the Ulm Campaign and a historic triumph at the Battle of Austerlitz, which led to the elimination of the Holy Roman Empire. In October 1805, however, a Franco-Spanish fleet was destroyed at the Battle of Trafalgar, allowing Britain to impose a naval blockade of the French coasts. In retaliation, Napoleon established the Continental System in 1806 to cut off European trade with Britain. The Fourth Coalition took up arms against him the same year because Prussia became worried about growing French influence on the continent. After quickly knocking out Prussia at the battles of Jena and Auerstedt, Napoleon turned his attention towards the Russians and annihilated them in 1807 at Friedland, which forced the Russians to accept the Treaties of Tilsit.

Hoping to extend the Continental System, Napoleon invaded Iberia and declared his brother Joseph the King of Spain in 1808. The Spanish and the Portuguese revolted with British support. The Peninsular War, noted for its brutal guerrilla warfare, lasted six years and culminated in an Allied victory. Fighting also erupted in Central Europe, as the Austrians launched another attack against the French in 1809. Napoleon defeated them at the Battle of Wagram, dissolving the Fifth Coalition formed against France. By 1811, Napoleon ruled over 70 million people across an empire that had domination in Europe, which had not witnessed this level of political consolidation since the days of the Roman Empire.[13] He maintained his strategic status through a series of alliances and family appointments. He created a new aristocracy in France while allowing the return of nobles who had been forced into exile by the Revolution.

Tensions over rising Polish nationalism and the economic effects of the Continental System led to renewed confrontation with Russia. To enforce his blockade, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia in 1812 that ended in catastrophic failure for the French. In 1813, Prussia and Austria joined Russian forces in a Sixth Coalition against France. A chaotic military campaign eventually culminated in a large Allied army defeating Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig in October. The next year, the Allies invaded France and captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April 1814. He was exiled to the island of Elba. The Bourbons were restored to power and the French lost most of the territories that they had conquered since the Revolution. However, Napoleon escaped from Elba in February 1815 and took control of the government once again. The Allies formed a Seventh Coalition, which ultimately defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in June. He was then captured by the British and imprisoned on the remote island of Saint Helena. His death in 1821 at the age of 51 was received by shock and grief throughout Europe. In 1840, a million people witnessed his remains returning to Paris, where they still reside at Les Invalides.[14]

Contents [hide]

1Origins and education

2Early career

2.1Siege of Toulon

2.213 Vendémiaire

2.3First Italian campaign

2.4Egyptian expedition

3Ruler of France

3.1French Consulate

3.1.1Temporary peace in Europe

3.2French Empire

3.2.1War of the Third Coalition

3.2.2Middle-Eastern alliances

3.2.3War of the Fourth Coalition and Tilsit

3.2.4Peninsular War and Erfurt

3.2.5War of the Fifth Coalition and Marie Louise

3.2.6Invasion of Russia

3.2.7War of the Sixth Coalition

3.2.8Exile to Elba

3.2.9Hundred Days

4Exile on Saint Helena

4.1Death

4.1.1Cause of death

5Religions

5.1Concordat

5.2Religious emancipation

6Personality

7Image

8Reforms

8.1Napoleonic Code

8.2Warfare

8.3Metric system

8.4Education

9Memory and evaluation

9.1Criticism

9.2Propaganda and memory

9.3Long-term impact outside France

10Marriages and children

11Titles, styles, honours, and arms

12Ancestry

13Notes

14Citations

15References

15.1Biographical studies

15.2Specialty studies

15.3Historiography and memory

16External links

Origins and education

Half-length portrait of a wigged middle-aged man with a well-to-do jacket. His left hand is tucked inside his waistcoat.

Napoleons father Carlo Buonaparte was Corsicas representative to the court of Louis XVI of France.

Napoleon was born on 15 August 1769, to Carlo Maria di Buonaparte and Maria Letizia Ramolino, in his familys ancestral home Casa Buonaparte in Ajaccio, the capital of the island of Corsica. He was their fourth child and third son. This was a year after the island was transferred to France by the Republic of Genoa.[15] He was christened Napoleone di Buonaparte, probably named after an uncle (an older brother who did not survive infancy was the first of the sons to be called Napoleone). In his 20s, he adopted the more French-sounding Napoléon Bonaparte.[16][note 2]

The Corsican Buonapartes were descended from minor Italian nobility of Tuscan origin, who had come to Corsica from Liguria in the 16th century.[17][18]

Head and shoulders portrait of a white-haired, portly, middle-aged man with a pinkish complexion, blue velvet coat, and a ruffle

The nationalist Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli; portrait by Richard Cosway, 1798

His father Nobile Carlo Buonaparte was an attorney, and was named Corsicas representative to the court of Louis XVI in 1777. The dominant influence of Napoleons childhood was his mother, Letizia Ramolino, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child.[19] Napoleons maternal grandmother had married into the Swiss Fesch family in her second marriage, and Napoleons uncle, the later cardinal Joseph Fesch, would fulfill the role as protector of the Bonaparte family for some years.

He had an elder brother Joseph, and younger siblings: Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline, and Jérôme. A boy and girl were born before Joseph but died in infancy. Napoleon was baptised as a Catholic.[20]

Napoleons noble, moderately affluent background afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time.[21] In January 1779, he was enrolled at a religious school in Autun. In May, he was admitted to a military academy at Brienne-le-Château.[22] His mother language was Corsican, and he always spoke French with a marked Corsican accent and never learned to spell French properly.[23] He was teased by other students for his accent and applied himself to reading.[24] An examiner observed that Napoleon has always been distinguished for his application in mathematics. He is fairly well acquainted with history and geography... This boy would make an excellent sailor.[25][note 3]

On completion of his studies at Brienne in 1784, Napoleon was admitted to the elite École Militaire in Paris. He trained to become an artillery officer and, when his fathers death reduced his income, was forced to complete the two-year course in one year.[27] He was the first Corsican to graduate from the École Militaire.[27] He was examined by the famed scientist Pierre-Simon Laplace.[28]

Early career

Napoleon Bonaparte, aged 23, Lieutenant-Colonel of a battalion of Corsican Republican volunteers

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment.[22][note 4] He served in Valence and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, and took nearly two years leave in Corsica and Paris during this period. He was a fervent Corsican nationalist, and wrote to Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli in May 1789, As the nation was perishing I was born. Thirty thousand Frenchmen were vomited on to our shores, drowning the throne of liberty in waves of blood. Such was the odious sight which was the first to strike me.[30]

He spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. He supported the Jacobin faction and gained command over a battalion of volunteers. He was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792, despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against a French army in Corsica.[31]

He returned to Corsica and came into conflict with Paoli, who had decided to split with France and sabotage the French assault on the Sardinian island of La Maddalena.[32] Bonaparte and his family fled to the French mainland in June 1793 because of the split with Paoli.[33]

Siege of Toulon

Main article: Siege of Toulon

Bonaparte at the Siege of Toulon

In July 1793, Bonaparte published a pro-republican pamphlet entitled Le souper de Beaucaire (Supper at Beaucaire) which gained him the support of Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of the Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. With the help of his fellow Corsican Antoine Christophe Saliceti, Bonaparte was appointed artillery commander of the republican forces at the siege of Toulon.[34]

He adopted a plan to capture a hill where republican guns could dominate the citys harbour and force the British to evacuate. The assault on the position led to the capture of the city, but during it Bonaparte was wounded in the thigh. He was promoted to brigadier general at the age of 24. Catching the attention of the Committee of Public Safety, he was put in charge of the artillery of Frances Army of Italy.[35]

Napoleon spent time as inspector of coastal fortifications on the Mediterranean coast near Marseille while he was waiting for confirmation of the Army of Italy post. He devised plans for attacking the Kingdom of Sardinia as part of Frances campaign against the First Coalition.[36] Augustin Robespierre and Saliceti were ready to listen to the freshly promoted artillery general.[37]

The French army carried out Bonapartes plan in the Battle of Saorgio in April 1794, and then advanced to seize Ormea in the mountains. From Ormea, they thrust west to outflank the Austro-Sardinian positions around Saorge. Later, Augustin Robespierre sent Bonaparte on a mission to the Republic of Genoa to determine that countrys intentions towards France.[36]

13 Vendémiaire

Main article: 13 Vendémiaire

Some contemporaries alleged that Bonaparte was put under house arrest at Nice for his association with the Robespierres following their fall in the Thermidorian Reaction in July 1794, but Napoleons secretary Bourrienne disputed the allegation in his memoirs. According to Bourrienne, jealousy was responsible, between the Army of the Alps and the Army of Italy (with whom Napoleon was seconded at the time).[38] Bonaparte dispatched an impassioned defense in a letter to representants Salicetti and Albitte, and subsequently he was acquitted of any wrongdoing.[39]

He was released within two weeks and, due to his technical skills, was asked to draw up plans to attack Italian positions in the context of Frances war with Austria. He also took part in an expedition to take back Corsica from the British, but the French were repulsed by the Royal Navy.[40]

By 1795, Bonaparte had become engaged to Désirée Clary, daughter of François Clary. Désirées sister Julie Clary had married Bonapartes elder brother Joseph.[41] In April 1795, he was assigned to the Army of the West, which was engaged in the War in the Vendée—a civil war and royalist counter-revolution in Vendée, a region in west central France on the Atlantic Ocean. As an infantry command, it was a demotion from artillery general—for which the army already had a full quota—and he pleaded poor health to avoid the posting.[42]

Etching of a street, there are a lot pockets of smoke due to a group of republican artillery firing on royalists across the street at the entrance to a building

Journée du 13 Vendémiaire. Artillery fire in front of the Church of Saint-Roch, Paris, Rue Saint-Honoré

He was moved to the Bureau of Topography of the Committee of Public Safety and sought unsuccessfully to be transferred to Constantinople in order to offer his services to the Sultan.[43] During this period, he wrote the romantic novella Clisson et Eugénie, about a soldier and his lover, in a clear parallel to Bonapartes own relationship with Désirée.[44] On 15 September, Bonaparte was removed from the list of generals in regular service for his refusal to serve in the Vendée campaign. He faced a difficult financial situation and reduced career prospects.[45]

On 3 October, royalists in Paris declared a rebellion against the National Convention.[46] Paul Barras, a leader of the Thermidorian Reaction, knew of Bonapartes military exploits at Toulon and gave him command of the improvised forces in defence of the Convention in the Tuileries Palace. Napoleon had seen the massacre of the Kings Swiss Guard there three years earlier and realised that artillery would be the key to its defence.[22]

He ordered a young cavalry officer named Joachim Murat to seize large cannons and used them to repel the attackers on 5 October 1795—13 Vendémiaire An IV in the French Republican Calendar. 1,400 royalists died and the rest fled.[46] He had cleared the streets with a whiff of grapeshot, according to 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History.[47][48]

The defeat of the royalist insurrection extinguished the threat to the Convention and earned Bonaparte sudden fame, wealth, and the patronage of the new government, the Directory. Murat married one of Napoleons sisters and became his brother-in-law; he also served under Napoleon as one of his generals. Bonaparte was promoted to Commander of the Interior and given command of the Army of Italy.[33]

Within weeks, he was romantically attached to Joséphine de Beauharnais, the former mistress of Barras. The couple married on 9 March 1796 in a civil ceremony.[49]

First Italian campaign

Main article: Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars

A three-quarter-length depiction of Bonaparte, with black tunic and leather gloves, holding a standard and sword, turning backwards to look at his troops

Bonaparte at the Pont dArcole, by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, (ca. 1801), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Two days after the marriage, Bonaparte left Paris to take command of the Army of Italy. He immediately went on the offensive, hoping to defeat the forces of Piedmont before their Austrian allies could intervene. In a series of rapid victories during the Montenotte Campaign, he knocked Piedmont out of the war in two weeks. The French then focused on the Austrians for the remainder of the war, the highlight of which became the protracted struggle for Mantua. The Austrians launched a series of offensives against the French to break the siege, but Napoleon defeated every relief effort, scoring notable victories at the battles of Castiglione, Bassano, Arcole, and Rivoli. The decisive French triumph at Rivoli in January 1797 led to the collapse of the Austrian position in Italy. At Rivoli, the Austrians lost up to 14,000 men while the French lost about 5,000.[50]

The next phase of the campaign featured the French invasion of the Habsburg heartlands. French forces in Southern Germany had been defeated by the Archduke Charles in 1796, but the Archduke withdrew his forces to protect Vienna after learning about Napoleons assault. In the first notable encounter between the two commanders, Napoleon pushed back his opponent and advanced deep into Austrian territory after winning at the Battle of Tarvis in March 1797. The Austrians were alarmed by the French thrust that reached all the way to Leoben, about 100 km from Vienna, and finally decided to sue for peace.[51] The Treaty of Leoben, followed by the more comprehensive Treaty of Campo Formio, gave France control of most of northern Italy and the Low Countries, and a secret clause promised the Republic of Venice to Austria. Bonaparte marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending 1,100 years of independence. He also authorized the French to loot treasures such as the Horses of Saint Mark.[52]

His application of conventional military ideas to real-world situations enabled his military triumphs, such as creative use of artillery as a mobile force to support his infantry. He remarked later in life: I have fought sixty battles and I have learned nothing which I did not know at the beginning. Look at Caesar; he fought the first like the last.[53]

Bonaparte could win battles by concealment of troop deployments and concentration of his forces on the hinge of an enemys weakened front. If he could not use his favourite envelopment strategy, he would take up the central position and attack two co-operating forces at their hinge, swing round to fight one until it fled, then turn to face the other.[54] In this Italian campaign, Bonapartes army captured 150,000 prisoners, 540 cannons, and 170 standards.[55] The French army fought 67 actions and won 18 pitched battles through superior artillery technology and Bonapartes tactics.[56]

During the campaign, Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics. He founded two newspapers: one for the troops in his army and another for circulation in France.[57] The royalists attacked Bonaparte for looting Italy and warned that he might become a dictator.[58] All told, Napoleons forces extracted an estimated $45 million in funds from Italy during their campaign there, another $12 million in precious metals and jewels; atop that, his forces confiscated more than three-hundred priceless paintings and sculptures.[59] Bonaparte sent General Pierre Augereau to Paris to lead a coup détat and purge the royalists on 4 September—Coup of 18 Fructidor. This left Barras and his Republican allies in control again but dependent on Bonaparte, who proceeded to peace negotiations with Austria. These negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Bonaparte returned to Paris in December as a hero.[60] He met Talleyrand, Frances new Foreign Minister—who later served in the same capacity for Emperor Napoleon—and they began to prepare for an invasion of Britain.

6229

Condition

Excellent

Buyer's Premium

- 0%

1798 1st American ed Napoleon Bonaparte in ITALY French

Estimate $450 - $1,000

20 bidders are watching this item.

Shipping & Pickup Options

Item located in Columbia, MO, usSee Policy for Shipping

Payment

Accepts seamless payments through LiveAuctioneers

Related Searches

TOP

![1596 FRENCH HISTORY Etienne PASQUIER antique FOLIO LES RECHERCHES DE LA FRANCE: LES RECHERCHES DE LA FRANCE, REVEUES & AUGMENTEES DE QUATRE LIVRES. by PASQUIER, Etienne Paris; 1596 Folio: 9 by 13.5" [4]-377 [ 379]-[16] ff. Monument of French historiography by the humanist magistr](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/5584/329751/177743911_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1715718131)

![19 issues of rare Gay Magazine METRA 1985-1986: [Queer interest], Metra: Midwest America's Leading Free Gay Magazine, 19 issues, published 1986-1987, a few duplicates, softcover, staplebound wraps, illustrated throughout in black and white, publish](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/184/328649/177016396_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1714770323)