M.C. Escher (Dutch, 1898-1972) Regular Division of the Plane I-VI (the complete set of six proofs),

M.C. Escher Sale History

View Price Results for M.C. EscherRelated Art

More Items from M.C. Escher

View More

Item Details

Description

M.C. Escher

(Dutch, 1898-1972)

Regular Division of the Plane I-VI (the complete set of six proofs), 1957

woodcuts printed in black

each signed in pencil

each 9 1/4 x 7 inches.

Literature:

Bool 416-421

Provenance:

Collection of R.J. Frisby, Oak Brook, Illinois

Thence by descent to the present owners

Lot Essay:

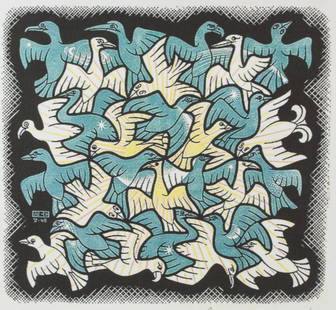

For Dutch artist M. C. Escher (1898-1972), tessellations were, “a real mania to which [he had] become addicted.”i Escher’s achievements at the intersection of mathematics and art with these regularly placed geometric designs are immediately recognizable and have been fascinating art collectors and mathematicians for generations. Hindman is pleased to offer a collection of six hand-signed woodcuts (Lot 162, Regular Division of the Plane I-VI (the complete set of six proofs)) that provide a unique insight to Escher’s working process for these tessellations, which he referred to as the regular division of the plane. These woodcuts illustrate the precision of form needed to balance the tension between nature and artifice within these dynamic compositions, elevating these works beyond mere wall decoration to unquestionable art form.

In 1956, the De Roos foundation—a bibliophilic society with a small private press—asked Escher to illustrate one of their upcoming publications. However, due to earlier dissatisfying illustration projects, Escher instead offered to write his own text for the foundation: an essay, Regelmatige vlakverdeling (Regular Division of the Plane), describing his process for tessellations, punctuated with these six woodcuts specifically made for the projectii. Finishing the prints in the spring of 1957, the book was published in 1958 in an edition of 175iii. It included three parts: the text, the six woodcut impressions in black and white, and the same six impressions printed in red that were detachable from the publication so that the reader could more fully reference the prints while reading. Unlike the black and white impressions culled directly from the original publication or the detachable red and white impressions, this set of the original proofs were each hand-signed by the artist in pencil and are rarely found complete. These proofs are the visual manifesto of Escher’s thought-process of the regular division of the plane and illustrate the gradual complexity of making such a tessellation through sequential panels.

The first two woodcuts show the sequence of Escher’s process. Woodcut I moves from primordial nothingness to a plane divided by geometric blocks shifting to a tessellation of birds and fish. The second compares early examples of tessellations found in Spain and Japan (numbered A, B, and C) to Escher’s more complex examples (numbered 1,2, and 3). While these cultures had early examples of tessellations, Escher found these attempts to be “rudimentary and embryonic.”iv Escher elevated the form to artwork first by using animate forms—the much more difficult animals, insects, and people compared to decorative repeating shapes—while also working to include a clearer sense of composition, seen in the remaining four woodcuts of dogs, riders, frogs and beetles, and lizards. The riders and dogs (woodcuts III and IV, respectively) share a similar compositional structure.

In woodcut III, for example, horizontal rows of interlocking horses and riders fill the page, each respective row in alternating black and white. As riders approach the upper and lower margins, they are delineated in increasingly less detail, until there are only white rider-shaped cutouts at the top and black at the bottom. This leads to a crescendo of activity in the center of the composition where the central two rows of riders interact. As described by Escher: “The flat shape irritates me—I feel like telling my objects, you are too fictious, lying there next to each other static and frozen: do something, come off the paper and show me what you are capable of! So I make them come out of the plane.”v Meanwhile, the edges of the scene are defined by vertical black and white lines so that there is no extraneous black or white space in the composition; the entirety of available positive and negative space is applied to the purpose of creating the horse-and-rider effect. This purposeful economy of space, color, and form was crucial to Escher’s working practice for printmaking. Of this print series for the Regular Division of the Plane, he noted that “The fact that I have restricted myself in this essay to white and black accords very well with my propensity for a ‘dualistic’ outlook. I have hardly ever experienced the pleasure of the artist who uses colour for its own sake; I use colour only when the nature of my shapes makes it necessary or when I am forced to do so by the fact that there are more than two motifs.vi” These proof impressions, in their use of black ink instead of the red used in the detachable impressions offered in the final De Roos publication, stress Escher’s original intentions and philosophy for his tessellations.

Woodcut V is similar to the dogs and riders in its emphasis of a kaleidoscope of activity in the center of the composition that tapers off at the upper and lower margins; but, rather than the same repeating motif, this woodcut shows black beetles at the top morphing into white frogs at the lower margin. The final woodcut of six repeating lizards constructing a triumphal arch is an impressive capstone to the series. It showcases the possibilities of tessellations for Escher, playing with the scale of the lizards to create the remarkable arch form. This work, and indeed the entire series, illustrates Escher’s opinions on balancing positive and negative space through color and line and the importance of utilizing dynamic animate forms to create compelling tessellated compositions. Thus, through these six proofs, the viewer is offered a unique entry into Escher’s fascinating imaginary world made possible through the regular division of the plane.

Bibliography

Bool, F.H., M. C. Escher: His Life and Complete Graphic Work. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1992.

Kersten, Erik. “The Regular Division of the Plane at the ‘De Roos’ foundation.” Escher in Het Paleis, September 12, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/the-regular-division-of-the-plane-at-the-de-roos-foundation/?lang=en.

(Dutch, 1898-1972)

Regular Division of the Plane I-VI (the complete set of six proofs), 1957

woodcuts printed in black

each signed in pencil

each 9 1/4 x 7 inches.

Literature:

Bool 416-421

Provenance:

Collection of R.J. Frisby, Oak Brook, Illinois

Thence by descent to the present owners

Lot Essay:

For Dutch artist M. C. Escher (1898-1972), tessellations were, “a real mania to which [he had] become addicted.”i Escher’s achievements at the intersection of mathematics and art with these regularly placed geometric designs are immediately recognizable and have been fascinating art collectors and mathematicians for generations. Hindman is pleased to offer a collection of six hand-signed woodcuts (Lot 162, Regular Division of the Plane I-VI (the complete set of six proofs)) that provide a unique insight to Escher’s working process for these tessellations, which he referred to as the regular division of the plane. These woodcuts illustrate the precision of form needed to balance the tension between nature and artifice within these dynamic compositions, elevating these works beyond mere wall decoration to unquestionable art form.

In 1956, the De Roos foundation—a bibliophilic society with a small private press—asked Escher to illustrate one of their upcoming publications. However, due to earlier dissatisfying illustration projects, Escher instead offered to write his own text for the foundation: an essay, Regelmatige vlakverdeling (Regular Division of the Plane), describing his process for tessellations, punctuated with these six woodcuts specifically made for the projectii. Finishing the prints in the spring of 1957, the book was published in 1958 in an edition of 175iii. It included three parts: the text, the six woodcut impressions in black and white, and the same six impressions printed in red that were detachable from the publication so that the reader could more fully reference the prints while reading. Unlike the black and white impressions culled directly from the original publication or the detachable red and white impressions, this set of the original proofs were each hand-signed by the artist in pencil and are rarely found complete. These proofs are the visual manifesto of Escher’s thought-process of the regular division of the plane and illustrate the gradual complexity of making such a tessellation through sequential panels.

The first two woodcuts show the sequence of Escher’s process. Woodcut I moves from primordial nothingness to a plane divided by geometric blocks shifting to a tessellation of birds and fish. The second compares early examples of tessellations found in Spain and Japan (numbered A, B, and C) to Escher’s more complex examples (numbered 1,2, and 3). While these cultures had early examples of tessellations, Escher found these attempts to be “rudimentary and embryonic.”iv Escher elevated the form to artwork first by using animate forms—the much more difficult animals, insects, and people compared to decorative repeating shapes—while also working to include a clearer sense of composition, seen in the remaining four woodcuts of dogs, riders, frogs and beetles, and lizards. The riders and dogs (woodcuts III and IV, respectively) share a similar compositional structure.

In woodcut III, for example, horizontal rows of interlocking horses and riders fill the page, each respective row in alternating black and white. As riders approach the upper and lower margins, they are delineated in increasingly less detail, until there are only white rider-shaped cutouts at the top and black at the bottom. This leads to a crescendo of activity in the center of the composition where the central two rows of riders interact. As described by Escher: “The flat shape irritates me—I feel like telling my objects, you are too fictious, lying there next to each other static and frozen: do something, come off the paper and show me what you are capable of! So I make them come out of the plane.”v Meanwhile, the edges of the scene are defined by vertical black and white lines so that there is no extraneous black or white space in the composition; the entirety of available positive and negative space is applied to the purpose of creating the horse-and-rider effect. This purposeful economy of space, color, and form was crucial to Escher’s working practice for printmaking. Of this print series for the Regular Division of the Plane, he noted that “The fact that I have restricted myself in this essay to white and black accords very well with my propensity for a ‘dualistic’ outlook. I have hardly ever experienced the pleasure of the artist who uses colour for its own sake; I use colour only when the nature of my shapes makes it necessary or when I am forced to do so by the fact that there are more than two motifs.vi” These proof impressions, in their use of black ink instead of the red used in the detachable impressions offered in the final De Roos publication, stress Escher’s original intentions and philosophy for his tessellations.

Woodcut V is similar to the dogs and riders in its emphasis of a kaleidoscope of activity in the center of the composition that tapers off at the upper and lower margins; but, rather than the same repeating motif, this woodcut shows black beetles at the top morphing into white frogs at the lower margin. The final woodcut of six repeating lizards constructing a triumphal arch is an impressive capstone to the series. It showcases the possibilities of tessellations for Escher, playing with the scale of the lizards to create the remarkable arch form. This work, and indeed the entire series, illustrates Escher’s opinions on balancing positive and negative space through color and line and the importance of utilizing dynamic animate forms to create compelling tessellated compositions. Thus, through these six proofs, the viewer is offered a unique entry into Escher’s fascinating imaginary world made possible through the regular division of the plane.

Bibliography

Bool, F.H., M. C. Escher: His Life and Complete Graphic Work. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1992.

Kersten, Erik. “The Regular Division of the Plane at the ‘De Roos’ foundation.” Escher in Het Paleis, September 12, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/the-regular-division-of-the-plane-at-the-de-roos-foundation/?lang=en.

Buyer's Premium

- 29% up to $400,000.00

- 24% up to $4,000,000.00

- 16% above $4,000,000.00

M.C. Escher (Dutch, 1898-1972) Regular Division of the Plane I-VI (the complete set of six proofs),

Estimate $15,000 - $25,000

56 bidders are watching this item.

Shipping & Pickup Options

Item located in Chicago, IL, usSee Policy for Shipping

Payment

TOP