1896 Karl MARX German Revolutions Communism Socialism

Similar Sale History

View More Items in Books

Related Books

More Items in Books

View MoreRecommended Books, Magazines & Papers

View More

Item Details

Description

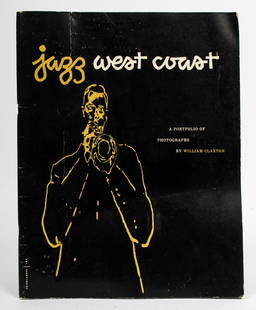

1896 Karl MARX German Revolutions Communism Socialism Philosophy Prussia Marxism

Karl Marx on the Revolution of German States in the middle of the 19th-century.

Karl Marx (1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. Born in Trier to a middle-class family, he later studied political economy and Hegelian philosophy. As an adult, Marx became stateless and spent much of his life in London, England, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German thinker Friedrich Engels and published various works, the most well-known being the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto. His work has since influenced subsequent intellectual, economic, and political history.

The revolutions of 1848–49 in the German states, the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (German: Märzrevolution), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated protests and rebellions in the states of the German Confederation, including the Austrian Empire. The revolutions, which stressed pan-Germanism, demonstrated popular discontent with the traditional, largely autocratic political structure of the thirty-nine independent states of the Confederation that inherited the German territory of the former Holy Roman Empire.

Item Number: #6126

Price: $299

Main author: Karl Marx; Karl Kautsky

Title: Revolution und kontre-Revolution in Deutschland

Published: Stuttgart : J.H.W. Dietz, 1896.

Language: German

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

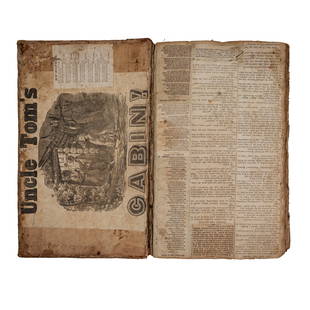

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure binding

Pages: complete with all XXX + 141 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: Stuttgart : J.H.W. Dietz, 1896.

Size: ~7.5in X 5in (19cm x 13cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$299

Karl Marx[6] (/mɑːrks/;[7] German: [ˈkaɐ̯l ˈmaɐ̯ks]; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. Born in Trier to a middle-class family, he later studied political economy and Hegelian philosophy. As an adult, Marx became stateless and spent much of his life in London, England, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German thinker Friedrich Engels and published various works, the most well-known being the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto. His work has since influenced subsequent intellectual, economic, and political history.

Marx's theories about society, economics and politics—collectively understood as Marxism—hold that human societies develop through class struggle; in capitalism, this manifests itself in the conflict between the ruling classes (known as the bourgeoisie) that control the means of production and working classes (known as the proletariat) that enable these means by selling their labour for wages. Through his theories of alienation, value, commodity fetishism, and surplus value, Marx argued that capitalism facilitated social relations and ideology through commodification, inequality, and the exploitation of labour. Employing a critical approach known as historical materialism, Marx propounded the theory of base and superstructure, asserting that the cultural and political conditions of society, as well as its notions of human nature, are largely determined by obscured economic foundations. These economic critiques would result in influential works such as Capital, Volume I (1867).

According to Marx, states are run in the interests of the ruling class but are nonetheless represented as being in favor of the common interest of all.[8] He predicted that, like previous socioeconomic systems, capitalism produced internal tensions which would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system: socialism. For Marx, class antagonisms under capitalism, owing in part to its instability and crisis-prone nature, would eventuate the working class' development of class consciousness, leading to their conquest of political power and eventually the establishment of a classless, communist society governed by a free association of producers.[9][10] Marx actively fought for its implementation, arguing that the working class should carry out organised revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio-economic emancipation.[11]

Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history, and his work has been both lauded and criticised.[12] His work in economics laid the basis for much of the current understanding of labour and its relation to capital, and subsequent economic thought.[13][14][15][16] Many intellectuals, labour unions, artists and political parties worldwide have been influenced by Marx's work, with many modifying or adapting his ideas. Marx is typically cited as one of the principal architects of modern sociology[17] and social science.[18]

Contents [hide]

1Life

1.1Childhood and early education: 1818–1835

1.2Hegelianism and early activism: 1836–1843

1.3Paris: 1843–1845

1.4Brussels: 1845–1848

1.5Cologne: 1848–1849

1.6Move to London and further writing: 1850–1860

1.7New York Tribune and journalism

1.8The First International and Capital

2Personal life

2.1Family

2.2Health

2.3Death

3Thought

3.1Influences

3.2Philosophy and social thought

3.2.1Human nature

3.2.2Labour, class struggle, and false consciousness

3.2.3Economy, history, and society

4Legacy

5Selected bibliography

6See also

7Notes

8References

8.1Bibliography

9Further reading

9.1Biographies

9.2Commentaries on Marx

9.3Medical articles

10External links

10.1Articles and entries

Life

Childhood and early education: 1818–1835

Karl Marx was born on 5 May 1818 to Heinrich Marx and Henrietta Pressburg (1788–1863). He was born at Brückengasse 664 in Trier, a town then part of the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of the Lower Rhine.[19] Marx was ancestrally Jewish; his maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi, while his paternal line had supplied Trier's rabbis since 1723, a role taken by his grandfather Meier Halevi Marx.[20] Karl's father, as a child known as Herschel, was the first in the line to receive a secular education; he became a lawyer and lived a relatively wealthy and middle-class existence, with his family owning a number of Moselle vineyards. Prior to his son's birth, and to escape the constraints of anti-semitic legislation, Herschel converted from Judaism to Lutheranism, the main Protestant denomination in Germany and Prussia at the time, taking on the German forename of Heinrich over the Yiddish Herschel.[21] Marx was also a third cousin once removed of German Romantic poet Heinrich Heine, also born to a German Jewish family in the Rhineland, with whom he became a frequent correspondent in later life.[22][page needed]

Marx's birthplace, now Brückenstrasse 10, Trier. It was purchased by the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1928 and now houses a museum devoted to him.[23]

Largely non-religious, Heinrich was a man of the Enlightenment, interested in the ideas of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. A classical liberal, he took part in agitation for a constitution and reforms in Prussia, then governed by an absolute monarchy.[24] In 1815 Heinrich Marx began work as an attorney, in 1819 moving his family to a ten-room property near the Porta Nigra.[25] His wife, a Dutch Jewish woman, Henriette Pressburg, was from a prosperous business family that later founded the company Philips Electronics: she was great-aunt to Anton and Gerard Philips, and great-great-aunt to Frits Philips. Her sister Sophie Pressburg (1797–1854), was Marx's aunt and was married to Lion Philips (1794–1866) Marx's uncle through this marriage, and was the grandmother of both Gerard and Anton Philips. Lion Philips was a wealthy Dutch tobacco manufacturer and industrialist, upon whom Karl and Jenny Marx would later often come to rely for loans while they were exiled in London.[26]

Little is known of Karl Marx's childhood.[27] The third of nine children, he became the oldest son when his brother Moritz died in 1819.[28] Young Karl was baptised into the Lutheran Church in August 1824 along with his surviving siblings, Sophie, Hermann, Henriette, Louise, Emilie and Caroline as was their mother the following year.[29] Young Karl was privately educated, by Heinrich Marx, until 1830, when he entered Trier High School, whose headmaster, Hugo Wyttenbach, was a friend of his father. By employing many liberal humanists as teachers, Wyttenbach incurred the anger of the local conservative government. Subsequently, police raided the school in 1832, and discovered that literature espousing political liberalism was being distributed among the students. Considering the distribution of such material a seditious act, the authorities instituted reforms and replaced several staff during Marx's attendance.[30]

In October 1835 at the age of 17, Marx travelled to the University of Bonn wishing to study philosophy and literature; however, his father insisted on law as a more practical field.[31] Due to a condition referred to as a "weak chest",[32] Karl was excused from military duty when he turned 18. While at the University at Bonn, Marx joined the Poets' Club, a group containing political radicals that were monitored by the police.[33] Marx also joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society (Landsmannschaft der Treveraner), at one point serving as club co-president.[34] Additionally, Marx was involved in certain disputes, some of which became serious: in August 1836 he took part in a duel with a member of the university's Borussian Korps.[35] Although his grades in the first term were good, they soon deteriorated, leading his father to force a transfer to the more serious and academic University of Berlin.[36]

Hegelianism and early activism: 1836–1843

Spending summer and autumn 1836 in Trier, Marx became more serious about his studies and his life. He became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, an educated baroness of the Prussian ruling class who had known Marx since childhood. As she had broken off her engagement with a young aristocrat to be with Marx, their relationship was socially controversial owing to the differences between their religious and class origins, but Marx befriended her father, a liberal aristocrat, Ludwig von Westphalen, and later dedicated his doctoral thesis to him.[37] Seven years after their engagement, on 19 June 1843, Marx married Jenny in a Protestant church in Kreuznach.[38]

In October 1836 Marx arrived in Berlin, matriculating in the university's faculty of law and renting a room in the Mittelstrasse.[39] Although studying law, he was fascinated by philosophy, and looked for a way to combine the two, believing that "without philosophy nothing could be accomplished".[40] Marx became interested in the recently deceased German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whose ideas were then widely debated among European philosophical circles.[41] During a convalescence in Stralau, he joined the Doctor's Club (Doktorklub), a student group which discussed Hegelian ideas, and through them became involved with a group of radical thinkers known as the Young Hegelians in 1837; they gathered around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, with Marx developing a particularly close friendship with Adolf Rutenberg. Like Marx, the Young Hegelians were critical of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions, but adopted his dialectical method in order to criticise established society, politics, and religion from a leftist perspective.[42] Marx's father died in May 1838, resulting in a diminished income for the family.[43] Marx had been emotionally close to his father, and treasured his memory after his death.[44]

Jenny von Westphalen in the 1830s

By 1837, Marx was writing both fiction and non-fiction, having completed a short novel, Scorpion and Felix, a drama, Oulanem, and a number of love poems dedicated to Jenny von Westphalen, though none of this early work was published during his lifetime.[45] Marx soon abandoned fiction for other pursuits, including the study of both English and Italian, art history and the translation of Latin classics.[46] He began co-operating with Bruno Bauer on editing Hegel's Philosophy of Religion in 1840. Marx was also engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature,[47] which he completed in 1841. It was described as "a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy":[48] The essay was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided, instead, to submit his thesis to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his PhD in April 1841.[49] As Marx and Bauer were both atheists, in March 1841 they began plans for a journal entitled Archiv des Atheismus (Atheistic Archives), but it never came to fruition. In July, Marx and Bauer took a trip to Bonn from Berlin. There they scandalised their class by getting drunk, laughing in church, and galloping through the streets on donkeys.[50]

Marx was considering an academic career, but this path was barred by the government's growing opposition to classical liberalism and the Young Hegelians.[51] Marx moved to Cologne in 1842, where he became a journalist, writing for the radical newspaper Rheinische Zeitung ("Rhineland News"), expressing his early views on socialism and his developing interest in economics. He criticised both right-wing European governments as well as figures in the liberal and socialist movements whom he thought ineffective or counter-productive.[52] The newspaper attracted the attention of the Prussian government censors, who checked every issue for seditious material before printing; Marx lamented that "Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at, and if the police nose smells anything un-Christian or un-Prussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear."[53] After the Rheinische Zeitung published an article strongly criticising the Russian monarchy, Tsar Nicholas I requested it be banned; Prussia's government complied in 1843.[54]

Paris: 1843–1845

In 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new, radical leftist Parisian newspaper, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals), then being set up by the German socialist Arnold Ruge to bring together German and French radicals,[55] and thus Marx and his wife moved to Paris in October 1843. Initially living with Ruge and his wife communally at 23 Rue Vaneau, they found the living conditions difficult, so moved out following the birth of their daughter Jenny in 1844.[56] Although intended to attract writers from both France and the German states, the Jahrbücher was dominated by the latter; the only non-German writer was the exiled Russian anarchist collectivist Mikhail Bakunin.[57] Marx contributed two essays to the paper, "Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right"[58] and "On the Jewish Question,"[59] the latter introducing his belief that the proletariat were a revolutionary force and marking his embrace of communism.[60] Only one issue was published, but it was relatively successful, largely owing to the inclusion of Heinrich Heine's satirical odes on King Ludwig of Bavaria, leading the German states to ban it and seize imported copies; Ruge nevertheless refused to fund the publication of further issues, and his friendship with Marx broke down.[61] After the paper's collapse, Marx began writing for the only uncensored German-language radical newspaper left, Vorwärts! (Forward!). Based in Paris, the paper was connected to the League of the Just, a utopian socialist secret society of workers and artisans. Marx attended some of their meetings, but did not join.[62] In Vorwärts!, Marx refined his views on socialism based upon Hegelian and Feuerbachian ideas of dialectical materialism, at the same time criticising liberals and other socialists operating in Europe.[63]

Friedrich Engels, whom Marx met in 1844; they became lifelong friends and collaborators.

On 28 August 1844, Marx met the German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence, beginning a lifelong friendship.[64] Engels showed Marx his recently published The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844,[65][66] convincing Marx that the working class would be the agent and instrument of the final revolution in history.[4][67] Soon Marx and Engels were collaborating on a criticism of the philosophical ideas of Marx's former friend, Bruno Bauer. This work was published in 1845 as The Holy Family.[68][69] Although critical of Bauer, Marx was increasingly influenced by the ideas of the Young Hegelians Max Stirner and Ludwig Feuerbach, but eventually Marx and Engels abandoned Feuerbachian materialism as well.[70]

During the time that he lived at 38 Rue Vanneau in Paris (from October 1843 until January 1845),[71] Marx engaged in an intensive study of "political economy" (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Mill etc.[72]), the French socialists (especially Claude Henri St. Simon and Charles Fourier)[73] and the history of France."[74] The study of political economy is a study that Marx would pursue for the rest of his life[75] and would result in his major economic work—the three-volume series called Capital.[76] Marxism is based in large part on three influences: Hegel's dialectics, French utopian socialism and English economics. Together with his earlier study of Hegel's dialectics, the studying that Marx did during this time in Paris meant that all major components of "Marxism" (or political economy as Marx called it) were in place by the autumn of 1844.[77] Although Marx was constantly being pulled away from his study of political economy by the usual daily demands on his time that everyone faces, and the additional special demands of editing a radical newspaper and later by the demands of organising and directing the efforts of a political party during years in which popular uprisings of the citizenry might at any moment become a revolution, Marx was always drawn back to his economic studies. Marx sought "to understand the inner workings of capitalism".[78]

An outline of "Marxism" had definitely formed in the mind of Karl Marx by late 1844. Indeed, many features of the Marxist view of the world's political economy had been worked out in great detail. However, Marx needed to write down all of the details of his economic world view to further clarify the new economic theory in his own mind.[79] Accordingly, Marx wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts.[80] These manuscripts covered numerous topics, detailing Marx's concept of alienated labour.[81] However, by the spring of 1845 his continued study of political economy, capital and capitalism had led Marx to the belief that the new political economic theory that he was espousing—scientific socialism—needed to be built on the base of a thoroughly developed materialistic view of the world.[82]

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 had been written between April and August 1844. Soon, though, Marx recognised that the Manuscripts had been influenced by some inconsistent ideas of Ludwig Feuerbach. Accordingly, Marx recognised the need to break with Feuerbach's philosophy in favour of historical materialism. Thus, a year later, in April 1845, after moving from Paris to Brussels, Marx wrote his eleven "Theses on Feuerbach,"[83] The "Theses on Feuerbach" are best known for Thesis 11, which states that "philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it".[81][84] This work contains Marx's criticism of materialism (for being contemplative), idealism (for reducing practice to theory) overall, criticising philosophy for putting abstract reality above the physical world.[81] It thus introduced the first glimpse at Marx's historical materialism, an argument that the world is changed not by ideas but by actual, physical, material activity and practice.[81][85] In 1845, after receiving a request from the Prussian king, the French government shut down Vorwärts!, with the interior minister, François Guizot, expelling Marx from France.[86] At this point, Marx moved from Paris to Brussels, where Marx hoped to, once again, continue his study of capitalism and political economy.

Brussels: 1845–1848

The first edition of The Manifesto of the Communist Party, published in German in 1848

Unable either to stay in France or to move to Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Brussels in Belgium in February 1845. However, to stay in Belgium, Marx had to pledge not to publish anything on the subject of contemporary politics.[86] In Brussels, he associated with other exiled socialists from across Europe, including Moses Hess, Karl Heinzen, and Joseph Weydemeyer, and soon, in April 1845, Engels moved from Barmen in Germany to Brussels to join Marx and the growing cadre of members of the League of the Just now seeking home in Brussels.[86][87] Later, Mary Burns, Engels' long-time companion, left Manchester, England, to join Engels in Brussels.[88]

In mid-July 1845, Marx and Engels left Brussels for England to visit the leaders of the Chartists, a socialist movement in Britain. This was Marx's first trip to England and Engels was an ideal guide for the trip. Engels had already spent two years living in Manchester, from November 1842[89] to August 1844.[90] Not only did Engels already know the English language,[91] he had developed a close relationship with many Chartist leaders.[91] Indeed, Engels was serving as a reporter for many Chartist and socialist English newspapers.[91] Marx used the trip as an opportunity to examine the economic resources available for study in various libraries in London and Manchester.[92]

In collaboration with Engels, Marx also set about writing a book which is often seen as his best treatment of the concept of historical materialism, The German Ideology.[93] In this work, Marx broke with Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner and the rest of the Young Hegelians, and also broke with Karl Grun and other "true socialists" whose philosophies were still based in part on "idealism". In German Ideology Marx and Engels finally completed their philosophy, which was based solely on materialism as the sole motor force in history.[94]

German Ideology is written in a humorously satirical form. But even this satirical form did not save the work from censorship. Like so many other early writings of his, German Ideology would not be published in Marx's lifetime and would be published only in 1932.[81][95][96]

After completing German Ideology, Marx turned to a work that was intended to clarify his own position regarding "the theory and tactics" of a truly "revolutionary proletarian movement" operating from the standpoint of a truly "scientific materialist" philosophy.[97] This work was intended to draw a distinction between the utopian socialists and Marx's own scientific socialist philosophy. Whereas the utopians believed that people must be persuaded one person at a time to join the socialist movement, the way a person must be persuaded to adopt any different belief, Marx knew that people would tend on most occasions to act in accordance with their own economic interests. Thus, appealing to an entire class (the working class in this case) with a broad appeal to the class's best material interest would be the best way to mobilise the broad mass of that class to make a revolution and change society. This was the intent of the new book that Marx was planning. However, to get the manuscript past the government censors, Marx called the book The Poverty of Philosophy (1847)[98] and offered it as a response to the "petty bourgeois philosophy" of the French anarchist socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as expressed in his book The Philosophy of Poverty

6126

Karl Marx on the Revolution of German States in the middle of the 19th-century.

Karl Marx (1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. Born in Trier to a middle-class family, he later studied political economy and Hegelian philosophy. As an adult, Marx became stateless and spent much of his life in London, England, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German thinker Friedrich Engels and published various works, the most well-known being the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto. His work has since influenced subsequent intellectual, economic, and political history.

The revolutions of 1848–49 in the German states, the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (German: Märzrevolution), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated protests and rebellions in the states of the German Confederation, including the Austrian Empire. The revolutions, which stressed pan-Germanism, demonstrated popular discontent with the traditional, largely autocratic political structure of the thirty-nine independent states of the Confederation that inherited the German territory of the former Holy Roman Empire.

Item Number: #6126

Price: $299

Main author: Karl Marx; Karl Kautsky

Title: Revolution und kontre-Revolution in Deutschland

Published: Stuttgart : J.H.W. Dietz, 1896.

Language: German

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure binding

Pages: complete with all XXX + 141 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: Stuttgart : J.H.W. Dietz, 1896.

Size: ~7.5in X 5in (19cm x 13cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$299

Karl Marx[6] (/mɑːrks/;[7] German: [ˈkaɐ̯l ˈmaɐ̯ks]; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. Born in Trier to a middle-class family, he later studied political economy and Hegelian philosophy. As an adult, Marx became stateless and spent much of his life in London, England, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German thinker Friedrich Engels and published various works, the most well-known being the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto. His work has since influenced subsequent intellectual, economic, and political history.

Marx's theories about society, economics and politics—collectively understood as Marxism—hold that human societies develop through class struggle; in capitalism, this manifests itself in the conflict between the ruling classes (known as the bourgeoisie) that control the means of production and working classes (known as the proletariat) that enable these means by selling their labour for wages. Through his theories of alienation, value, commodity fetishism, and surplus value, Marx argued that capitalism facilitated social relations and ideology through commodification, inequality, and the exploitation of labour. Employing a critical approach known as historical materialism, Marx propounded the theory of base and superstructure, asserting that the cultural and political conditions of society, as well as its notions of human nature, are largely determined by obscured economic foundations. These economic critiques would result in influential works such as Capital, Volume I (1867).

According to Marx, states are run in the interests of the ruling class but are nonetheless represented as being in favor of the common interest of all.[8] He predicted that, like previous socioeconomic systems, capitalism produced internal tensions which would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system: socialism. For Marx, class antagonisms under capitalism, owing in part to its instability and crisis-prone nature, would eventuate the working class' development of class consciousness, leading to their conquest of political power and eventually the establishment of a classless, communist society governed by a free association of producers.[9][10] Marx actively fought for its implementation, arguing that the working class should carry out organised revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio-economic emancipation.[11]

Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history, and his work has been both lauded and criticised.[12] His work in economics laid the basis for much of the current understanding of labour and its relation to capital, and subsequent economic thought.[13][14][15][16] Many intellectuals, labour unions, artists and political parties worldwide have been influenced by Marx's work, with many modifying or adapting his ideas. Marx is typically cited as one of the principal architects of modern sociology[17] and social science.[18]

Contents [hide]

1Life

1.1Childhood and early education: 1818–1835

1.2Hegelianism and early activism: 1836–1843

1.3Paris: 1843–1845

1.4Brussels: 1845–1848

1.5Cologne: 1848–1849

1.6Move to London and further writing: 1850–1860

1.7New York Tribune and journalism

1.8The First International and Capital

2Personal life

2.1Family

2.2Health

2.3Death

3Thought

3.1Influences

3.2Philosophy and social thought

3.2.1Human nature

3.2.2Labour, class struggle, and false consciousness

3.2.3Economy, history, and society

4Legacy

5Selected bibliography

6See also

7Notes

8References

8.1Bibliography

9Further reading

9.1Biographies

9.2Commentaries on Marx

9.3Medical articles

10External links

10.1Articles and entries

Life

Childhood and early education: 1818–1835

Karl Marx was born on 5 May 1818 to Heinrich Marx and Henrietta Pressburg (1788–1863). He was born at Brückengasse 664 in Trier, a town then part of the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of the Lower Rhine.[19] Marx was ancestrally Jewish; his maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi, while his paternal line had supplied Trier's rabbis since 1723, a role taken by his grandfather Meier Halevi Marx.[20] Karl's father, as a child known as Herschel, was the first in the line to receive a secular education; he became a lawyer and lived a relatively wealthy and middle-class existence, with his family owning a number of Moselle vineyards. Prior to his son's birth, and to escape the constraints of anti-semitic legislation, Herschel converted from Judaism to Lutheranism, the main Protestant denomination in Germany and Prussia at the time, taking on the German forename of Heinrich over the Yiddish Herschel.[21] Marx was also a third cousin once removed of German Romantic poet Heinrich Heine, also born to a German Jewish family in the Rhineland, with whom he became a frequent correspondent in later life.[22][page needed]

Marx's birthplace, now Brückenstrasse 10, Trier. It was purchased by the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1928 and now houses a museum devoted to him.[23]

Largely non-religious, Heinrich was a man of the Enlightenment, interested in the ideas of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. A classical liberal, he took part in agitation for a constitution and reforms in Prussia, then governed by an absolute monarchy.[24] In 1815 Heinrich Marx began work as an attorney, in 1819 moving his family to a ten-room property near the Porta Nigra.[25] His wife, a Dutch Jewish woman, Henriette Pressburg, was from a prosperous business family that later founded the company Philips Electronics: she was great-aunt to Anton and Gerard Philips, and great-great-aunt to Frits Philips. Her sister Sophie Pressburg (1797–1854), was Marx's aunt and was married to Lion Philips (1794–1866) Marx's uncle through this marriage, and was the grandmother of both Gerard and Anton Philips. Lion Philips was a wealthy Dutch tobacco manufacturer and industrialist, upon whom Karl and Jenny Marx would later often come to rely for loans while they were exiled in London.[26]

Little is known of Karl Marx's childhood.[27] The third of nine children, he became the oldest son when his brother Moritz died in 1819.[28] Young Karl was baptised into the Lutheran Church in August 1824 along with his surviving siblings, Sophie, Hermann, Henriette, Louise, Emilie and Caroline as was their mother the following year.[29] Young Karl was privately educated, by Heinrich Marx, until 1830, when he entered Trier High School, whose headmaster, Hugo Wyttenbach, was a friend of his father. By employing many liberal humanists as teachers, Wyttenbach incurred the anger of the local conservative government. Subsequently, police raided the school in 1832, and discovered that literature espousing political liberalism was being distributed among the students. Considering the distribution of such material a seditious act, the authorities instituted reforms and replaced several staff during Marx's attendance.[30]

In October 1835 at the age of 17, Marx travelled to the University of Bonn wishing to study philosophy and literature; however, his father insisted on law as a more practical field.[31] Due to a condition referred to as a "weak chest",[32] Karl was excused from military duty when he turned 18. While at the University at Bonn, Marx joined the Poets' Club, a group containing political radicals that were monitored by the police.[33] Marx also joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society (Landsmannschaft der Treveraner), at one point serving as club co-president.[34] Additionally, Marx was involved in certain disputes, some of which became serious: in August 1836 he took part in a duel with a member of the university's Borussian Korps.[35] Although his grades in the first term were good, they soon deteriorated, leading his father to force a transfer to the more serious and academic University of Berlin.[36]

Hegelianism and early activism: 1836–1843

Spending summer and autumn 1836 in Trier, Marx became more serious about his studies and his life. He became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, an educated baroness of the Prussian ruling class who had known Marx since childhood. As she had broken off her engagement with a young aristocrat to be with Marx, their relationship was socially controversial owing to the differences between their religious and class origins, but Marx befriended her father, a liberal aristocrat, Ludwig von Westphalen, and later dedicated his doctoral thesis to him.[37] Seven years after their engagement, on 19 June 1843, Marx married Jenny in a Protestant church in Kreuznach.[38]

In October 1836 Marx arrived in Berlin, matriculating in the university's faculty of law and renting a room in the Mittelstrasse.[39] Although studying law, he was fascinated by philosophy, and looked for a way to combine the two, believing that "without philosophy nothing could be accomplished".[40] Marx became interested in the recently deceased German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whose ideas were then widely debated among European philosophical circles.[41] During a convalescence in Stralau, he joined the Doctor's Club (Doktorklub), a student group which discussed Hegelian ideas, and through them became involved with a group of radical thinkers known as the Young Hegelians in 1837; they gathered around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, with Marx developing a particularly close friendship with Adolf Rutenberg. Like Marx, the Young Hegelians were critical of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions, but adopted his dialectical method in order to criticise established society, politics, and religion from a leftist perspective.[42] Marx's father died in May 1838, resulting in a diminished income for the family.[43] Marx had been emotionally close to his father, and treasured his memory after his death.[44]

Jenny von Westphalen in the 1830s

By 1837, Marx was writing both fiction and non-fiction, having completed a short novel, Scorpion and Felix, a drama, Oulanem, and a number of love poems dedicated to Jenny von Westphalen, though none of this early work was published during his lifetime.[45] Marx soon abandoned fiction for other pursuits, including the study of both English and Italian, art history and the translation of Latin classics.[46] He began co-operating with Bruno Bauer on editing Hegel's Philosophy of Religion in 1840. Marx was also engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature,[47] which he completed in 1841. It was described as "a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy":[48] The essay was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided, instead, to submit his thesis to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his PhD in April 1841.[49] As Marx and Bauer were both atheists, in March 1841 they began plans for a journal entitled Archiv des Atheismus (Atheistic Archives), but it never came to fruition. In July, Marx and Bauer took a trip to Bonn from Berlin. There they scandalised their class by getting drunk, laughing in church, and galloping through the streets on donkeys.[50]

Marx was considering an academic career, but this path was barred by the government's growing opposition to classical liberalism and the Young Hegelians.[51] Marx moved to Cologne in 1842, where he became a journalist, writing for the radical newspaper Rheinische Zeitung ("Rhineland News"), expressing his early views on socialism and his developing interest in economics. He criticised both right-wing European governments as well as figures in the liberal and socialist movements whom he thought ineffective or counter-productive.[52] The newspaper attracted the attention of the Prussian government censors, who checked every issue for seditious material before printing; Marx lamented that "Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at, and if the police nose smells anything un-Christian or un-Prussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear."[53] After the Rheinische Zeitung published an article strongly criticising the Russian monarchy, Tsar Nicholas I requested it be banned; Prussia's government complied in 1843.[54]

Paris: 1843–1845

In 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new, radical leftist Parisian newspaper, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals), then being set up by the German socialist Arnold Ruge to bring together German and French radicals,[55] and thus Marx and his wife moved to Paris in October 1843. Initially living with Ruge and his wife communally at 23 Rue Vaneau, they found the living conditions difficult, so moved out following the birth of their daughter Jenny in 1844.[56] Although intended to attract writers from both France and the German states, the Jahrbücher was dominated by the latter; the only non-German writer was the exiled Russian anarchist collectivist Mikhail Bakunin.[57] Marx contributed two essays to the paper, "Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right"[58] and "On the Jewish Question,"[59] the latter introducing his belief that the proletariat were a revolutionary force and marking his embrace of communism.[60] Only one issue was published, but it was relatively successful, largely owing to the inclusion of Heinrich Heine's satirical odes on King Ludwig of Bavaria, leading the German states to ban it and seize imported copies; Ruge nevertheless refused to fund the publication of further issues, and his friendship with Marx broke down.[61] After the paper's collapse, Marx began writing for the only uncensored German-language radical newspaper left, Vorwärts! (Forward!). Based in Paris, the paper was connected to the League of the Just, a utopian socialist secret society of workers and artisans. Marx attended some of their meetings, but did not join.[62] In Vorwärts!, Marx refined his views on socialism based upon Hegelian and Feuerbachian ideas of dialectical materialism, at the same time criticising liberals and other socialists operating in Europe.[63]

Friedrich Engels, whom Marx met in 1844; they became lifelong friends and collaborators.

On 28 August 1844, Marx met the German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence, beginning a lifelong friendship.[64] Engels showed Marx his recently published The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844,[65][66] convincing Marx that the working class would be the agent and instrument of the final revolution in history.[4][67] Soon Marx and Engels were collaborating on a criticism of the philosophical ideas of Marx's former friend, Bruno Bauer. This work was published in 1845 as The Holy Family.[68][69] Although critical of Bauer, Marx was increasingly influenced by the ideas of the Young Hegelians Max Stirner and Ludwig Feuerbach, but eventually Marx and Engels abandoned Feuerbachian materialism as well.[70]

During the time that he lived at 38 Rue Vanneau in Paris (from October 1843 until January 1845),[71] Marx engaged in an intensive study of "political economy" (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Mill etc.[72]), the French socialists (especially Claude Henri St. Simon and Charles Fourier)[73] and the history of France."[74] The study of political economy is a study that Marx would pursue for the rest of his life[75] and would result in his major economic work—the three-volume series called Capital.[76] Marxism is based in large part on three influences: Hegel's dialectics, French utopian socialism and English economics. Together with his earlier study of Hegel's dialectics, the studying that Marx did during this time in Paris meant that all major components of "Marxism" (or political economy as Marx called it) were in place by the autumn of 1844.[77] Although Marx was constantly being pulled away from his study of political economy by the usual daily demands on his time that everyone faces, and the additional special demands of editing a radical newspaper and later by the demands of organising and directing the efforts of a political party during years in which popular uprisings of the citizenry might at any moment become a revolution, Marx was always drawn back to his economic studies. Marx sought "to understand the inner workings of capitalism".[78]

An outline of "Marxism" had definitely formed in the mind of Karl Marx by late 1844. Indeed, many features of the Marxist view of the world's political economy had been worked out in great detail. However, Marx needed to write down all of the details of his economic world view to further clarify the new economic theory in his own mind.[79] Accordingly, Marx wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts.[80] These manuscripts covered numerous topics, detailing Marx's concept of alienated labour.[81] However, by the spring of 1845 his continued study of political economy, capital and capitalism had led Marx to the belief that the new political economic theory that he was espousing—scientific socialism—needed to be built on the base of a thoroughly developed materialistic view of the world.[82]

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 had been written between April and August 1844. Soon, though, Marx recognised that the Manuscripts had been influenced by some inconsistent ideas of Ludwig Feuerbach. Accordingly, Marx recognised the need to break with Feuerbach's philosophy in favour of historical materialism. Thus, a year later, in April 1845, after moving from Paris to Brussels, Marx wrote his eleven "Theses on Feuerbach,"[83] The "Theses on Feuerbach" are best known for Thesis 11, which states that "philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it".[81][84] This work contains Marx's criticism of materialism (for being contemplative), idealism (for reducing practice to theory) overall, criticising philosophy for putting abstract reality above the physical world.[81] It thus introduced the first glimpse at Marx's historical materialism, an argument that the world is changed not by ideas but by actual, physical, material activity and practice.[81][85] In 1845, after receiving a request from the Prussian king, the French government shut down Vorwärts!, with the interior minister, François Guizot, expelling Marx from France.[86] At this point, Marx moved from Paris to Brussels, where Marx hoped to, once again, continue his study of capitalism and political economy.

Brussels: 1845–1848

The first edition of The Manifesto of the Communist Party, published in German in 1848

Unable either to stay in France or to move to Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Brussels in Belgium in February 1845. However, to stay in Belgium, Marx had to pledge not to publish anything on the subject of contemporary politics.[86] In Brussels, he associated with other exiled socialists from across Europe, including Moses Hess, Karl Heinzen, and Joseph Weydemeyer, and soon, in April 1845, Engels moved from Barmen in Germany to Brussels to join Marx and the growing cadre of members of the League of the Just now seeking home in Brussels.[86][87] Later, Mary Burns, Engels' long-time companion, left Manchester, England, to join Engels in Brussels.[88]

In mid-July 1845, Marx and Engels left Brussels for England to visit the leaders of the Chartists, a socialist movement in Britain. This was Marx's first trip to England and Engels was an ideal guide for the trip. Engels had already spent two years living in Manchester, from November 1842[89] to August 1844.[90] Not only did Engels already know the English language,[91] he had developed a close relationship with many Chartist leaders.[91] Indeed, Engels was serving as a reporter for many Chartist and socialist English newspapers.[91] Marx used the trip as an opportunity to examine the economic resources available for study in various libraries in London and Manchester.[92]

In collaboration with Engels, Marx also set about writing a book which is often seen as his best treatment of the concept of historical materialism, The German Ideology.[93] In this work, Marx broke with Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner and the rest of the Young Hegelians, and also broke with Karl Grun and other "true socialists" whose philosophies were still based in part on "idealism". In German Ideology Marx and Engels finally completed their philosophy, which was based solely on materialism as the sole motor force in history.[94]

German Ideology is written in a humorously satirical form. But even this satirical form did not save the work from censorship. Like so many other early writings of his, German Ideology would not be published in Marx's lifetime and would be published only in 1932.[81][95][96]

After completing German Ideology, Marx turned to a work that was intended to clarify his own position regarding "the theory and tactics" of a truly "revolutionary proletarian movement" operating from the standpoint of a truly "scientific materialist" philosophy.[97] This work was intended to draw a distinction between the utopian socialists and Marx's own scientific socialist philosophy. Whereas the utopians believed that people must be persuaded one person at a time to join the socialist movement, the way a person must be persuaded to adopt any different belief, Marx knew that people would tend on most occasions to act in accordance with their own economic interests. Thus, appealing to an entire class (the working class in this case) with a broad appeal to the class's best material interest would be the best way to mobilise the broad mass of that class to make a revolution and change society. This was the intent of the new book that Marx was planning. However, to get the manuscript past the government censors, Marx called the book The Poverty of Philosophy (1847)[98] and offered it as a response to the "petty bourgeois philosophy" of the French anarchist socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as expressed in his book The Philosophy of Poverty

6126

Condition

Excellent

Buyer's Premium

- 0%

1896 Karl MARX German Revolutions Communism Socialism

Estimate $299 - $600

14 bidders are watching this item.

Shipping & Pickup Options

Item located in Columbia, MO, usOffers In-House Shipping

Payment

Related Searches

TOP

![[Bible, in Low German, 1478]: Collection of leaves/sections from the first edition of the Bible in Low German, with glosses according to Nicolaus de Lyra. [Cologne: Heinrich Quentell, 1478.] 16.5" x 12". Includes 1 leaf from the b](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/3532/117365/60345179_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1519867546)

![[Judaica, German Jewish Life, 1748-9]: Bodenschatz, Georg Johann Christoph. KIRCHLICHE VERFASSUNG DER HEUTIGEN JUDEN, SONDERLICH DERER IN DEUTSCHLAND. Frankfurt and Leipzig: 1748-1749. 4to. [16], 206, 386; [16], 256, 270, [36] pp. + engrav](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/3532/154050/77745017_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1572759985)

![German Bible Compendium, 1622: German Bible Compendium, 1622 {Dimensions 4 1/4 x 10 3/4 x 7 1/2 inches} [not collated, owner's inscription, losses to leather binding, loose spine, handwritten notes throughout]](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/1098/103159/52841128_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1493331921)

![19 issues of rare Gay Magazine METRA 1985-1986: [Queer interest], Metra: Midwest America's Leading Free Gay Magazine, 19 issues, published 1986-1987, a few duplicates, softcover, staplebound wraps, illustrated throughout in black and white, publish](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/184/328649/177016396_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1714770323)