1737 History of Knights Templar Hospitaller of Saint J.

Similar Sale History

View More Items in Books, Magazines & Papers

Related Books, Magazines & Papers

More Items in Books, Magazines & Papers

View MoreRecommended Collectibles

View More

Item Details

Description

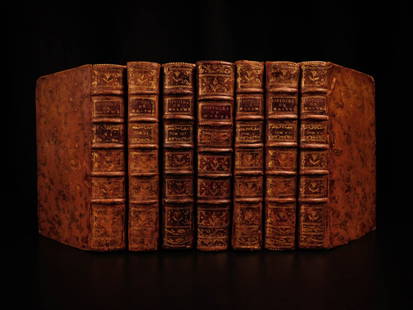

1737 History of Knights Templar Hospitaller of Saint John Crusades Malta Rhodes

VERY Desirable Complete Set with Fascinating Content

The Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Hospitallers, Order of Hospitallers, Knights of Saint John and Order of Saint John, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders during the Middle Ages.

Item number: #5902

Price: $750

Main author: Vertot, abbe de

Title: Histoire des chevaliers hospitaliers de S. Jean de JeÌrusalem, appelez depuis chevaliers de Rhodes et aujourdhui chevaliers de Malthe.

Published: Paris : Quillau, 1737. / complete 5v set

Language: French

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure leather binding

Pages: complete with all 608 + 502 + 563 + 540 + 484 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: Paris : Quillau, 1737.

Size: ~6.75in X 3.75in (17cm x 9.5cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our first priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$750

The Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Hospitallers, Order of Hospitallers, Knights of Saint John and Order of Saint John, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders during the Middle Ages.

The Hospitallers probably arose as a group of individuals associated with an Amalfitan hospital in the Muristan district of Jerusalem, which was dedicated to St John the Baptist and founded around 1023 by Blessed Gerard Thom to provide care for poor, sick or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land. (Some scholars, however, consider that the Amalfitan order and Amalfitan hospital were different from Gerards order and its hospital.[1]) After the Latin Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade, the organisation became a religious and military order under its own Papal charter, and it was charged with the care and defence of the Holy Land. Following the conquest of the Holy Land by Islamic forces, the Order operated from Rhodes, over which it was sovereign, and later from Malta where it administered a vassal state under the Spanish viceroy of Sicily.

The Order was weakened in the Reformation, when rich commanderies of the Order in northern Germany and the Netherlands became Protestant (and, largely separated from the Roman Catholic main stem, remain so to this day), and the Order was disestablished in England, Denmark, and elsewhere in northern Europe. The Roman Catholic order was further damaged by Napoleons capture of Malta in 1798 and became dispersed throughout Europe. It regained strength during the early 19th century as it redirected itself toward humanitarian and religious causes. In 1834, the order, by this time known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), acquired new headquarters in Rome where it has remained since. As of 2013, the Roman Catholic order has about 13,500 members, 80,000 volunteers, and 25,000 mostly medical employees,[2] and operates in about 120 countries across the world, including in Muslim nations; the Protestant branches of the order are smaller but engage in similar work. Until recently the order focused mainly on developing countries, but following the introduction of austerity in the Eurozone and the United Kingdom which began in 2010, they have increasingly turned their attention to Europe, establishing shelters and soup kitchens to help the homeless and those suffering from hunger.[3]

Five contemporary, state-recognised chivalric orders which claim modern inheritance of the Hospitaller tradition all assert that The Sovereign Military Order of Malta is the original order and that four non-Catholic orders stem from the same root:[4] Protestant orders exist in Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, and a non-denominational British revival is headquartered in the United Kingdom.

Contents [hide]

1 Foundation and early history

2 Knights of Cyprus and Rhodes

3 Knights of Malta

3.1 The Knights in the 16th and 17th centuries: Reconquista of the Sea

3.2 Life in Malta

3.3 Turmoil in Europe

3.4 The loss of Malta

4 Sovereign Military Order of Malta

5 Protestant continuation in continental Europe

6 Revival in Britain as the Venerable Order of St. John of Jerusalem

7 Mimic orders

8 Remnants

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Foundation and early history[edit]

Grand Master and senior Knights Hospitaller in the 14th century

In 623, Pope Gregory I commissioned the Ravennate Abbot Probus, who was previously Gregorys emissary at the Lombard court, to build a hospital in Jerusalem to treat and care for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land. In 800, Charlemagne, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, enlarged Probus hospital and added a library to it. About 200 years later, in 1005, Caliph Al Hakim destroyed the hospital and three thousand other buildings in Jerusalem. In 1023, merchants from Amalfi and Salerno in Italy were given permission by the Caliph Ali az-Zahir of Egypt to rebuild the hospital in Jerusalem. The hospital, which was built on the site of the monastery of Saint John the Baptist, took in Christian pilgrims travelling to visit the Christian holy sites. It was served by Benedictine monks.

The monastic hospitaller order was founded following the First Crusade by the Blessed Gerard, whose role as founder was confirmed by a Papal bull of Pope Paschal II in 1113.[2] Gerard acquired territory and revenues for his order throughout the Kingdom of Jerusalem and beyond. Under his successor, Raymond du Puy de Provence, the original hospice was expanded to an infirmary[1] near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Initially the group cared for pilgrims in Jerusalem, but the order soon extended to providing pilgrims with an armed escort, which soon grew into a substantial force. Thus the Order of St. John imperceptibly became military without losing its eleemosynary character.[1] The Hospitallers and the Knights Templar became the most formidable military orders in the Holy Land. Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, pledged his protection to the Knights of St. John in a charter of privileges granted in 1185.

The statutes of Roger de Moulins (1187) deal only with the service of the sick; the first mention of military service is in the statutes of the ninth grand master, Afonso of Portugal (about 1200). In the latter a marked distinction is made between secular knights, externs to the order, who served only for a time, and the professed knights, attached to the order by a perpetual vow, and who alone enjoyed the same spiritual privileges as the other religious. The order numbered three distinct classes of membership: the military brothers, the brothers infirmarians, and the brothers chaplains, to whom was entrusted the divine service.[1]

The order came to distinguish itself in battle with the Muslims, its soldiers wearing a black surcoat with a white cross. In 1248 Pope Innocent IV (1243–54), approved a standard military dress for the Hospitallers to be worn in battle. Instead of a closed cape over their armour (which restricted their movements) they should wear a red surcoat with a white cross emblazoned on it.[5]

Many of the more substantial Christian fortifications in the Holy Land were built by the Templars and the Hospitallers. At the height of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Hospitallers held seven great forts and 140 other estates in the area. The two largest of these, their bases of power in the Kingdom and in the Principality of Antioch, were the Krak des Chevaliers and Margat in Syria.[2] The property of the Order was divided into priories, subdivided into bailiwicks, which in turn were divided into commandries.

As early as the late 12th century the order had begun to achieve recognition in the Kingdom of England and Duchy of Normandy. As a result, buildings such as St Johns Jerusalem and the Knights Gate, Quenington in England were built on land donated to the order by local nobility.[6] An Irish house was established at Kilmainham, near Dublin, and the Irish Prior was usually a key figure in Irish public life.

Knights of Cyprus and Rhodes[edit]

Street of Knights in Rhodes

The Knights castle at Rhodes

Further information: Siege of Rhodes (1480) and Siege of Rhodes (1522)

The rising power of Islam eventually expelled the Knights from Jerusalem. After the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291 (Jerusalem itself fell in 1187), the Knights were confined to the County of Tripoli and, when Acre was captured in 1291, the order sought refuge in the Kingdom of Cyprus. Finding themselves becoming enmeshed in Cypriot politics, their Master, Guillaume de Villaret, created a plan of acquiring their own temporal domain, selecting Rhodes to be their new home, part of the Byzantine empire. His successor, Fulkes de Villaret, executed the plan, and on 15 August 1309, after over two years of campaigning, the island of Rhodes surrendered to the knights. They also gained control of a number of neighbouring islands and the Anatolian port of Bodrum and Kastelorizo.

Rhodes and other possessions of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John.

Pope Clement V dissolved the Hospitallers rival order, the Knights Templar, in 1312 with a series of papal bulls, including the Ad providam bull, which turned over much of their property to the Hospitallers. The holdings were organised into eight tongues (one each in Crown of Aragon, Auvergne, Castile, England, France, Germany, Italy, and Provence). Each was administered by a Prior or, if there was more than one priory in the tongue, by a Grand Prior. At Rhodes and later Malta, the resident knights of each tongue were headed by a Bailli. The English Grand Prior at the time was Philip De Thame, who acquired the estates allocated to the English tongue from 1330 to 1358. In 1334, the Knights of Rhodes defeated Andronicus and his Turkish auxiliaries. In the 14th century, there were several other battles in which they fought.[7]

On Rhodes the Hospitallers,[8] by then also referred to as the Knights of Rhodes,[9] were forced to become a more militarised force, fighting especially with the Barbary pirates. They withstood two invasions in the 15th century, one by the Sultan of Egypt in 1444 and another by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in 1480 who, after capturing Constantinople and defeating the Byzantine Empire in 1453, made the Knights a priority target.

In 1494 they created a stronghold on the peninsula of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum). They used pieces of the partially destroyed Mausoleum, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, to strengthen Bodrum Castle.[10]

In 1522, an entirely new sort of force arrived: 400 ships under the command of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent delivered 100,000 men to the island[11] (200,000 in other sources[12]). Against this force the Knights, under Grand Master Philippe Villiers de LIsle-Adam, had about 7,000 men-at-arms and their fortifications. The siege lasted six months, at the end of which the surviving defeated Hospitallers were allowed to withdraw to Sicily. Despite the defeat, both Christians and Muslims seem to have regarded the conduct of Villiers de LIsle-Adam as extremely valiant, and the Grand Master was proclaimed a Defender of the Faith by Pope Adrian VI.

Knights of Malta[edit]

See also: History of Malta under the Order of Saint John

Grand culverin of the Knights Hospitallers, 1500–1510, Rhodes. French work, caliber: 165 mm, length: 540 cm, weight: 3,343 kg, ammunition: 15kg iron ball. Arms of Grand Master Emery dAmboise. Given by Abdülaziz to Napoleon III in 1862.

Arms of the Knights Hospitallers, quartered with those of Pierre dAubusson, on a bombard ordered by the latter. The top inscription further reads: F. PETRUS DAUBUSSON M HOSPITALIS IHER.

After seven years of moving from place to place in Europe the Knights became established in 1530 when Charles I of Spain, as King of Sicily, gave them Malta,[13] Gozo and the North African port of Tripoli in perpetual fiefdom in exchange for an annual fee of a single Maltese falcon (Tribute of the Maltese Falcon), which they were to send on All Souls Day to the Kings representative, the Viceroy of Sicily,[14] (this historical fact was used as the plot hook in Dashiell Hammetts famous book The Maltese Falcon).

The Hospitallers continued their actions against the Muslims and especially the Barbary pirates. Although they had only a few ships they quickly drew the ire of the Ottomans, who were unhappy to see the order resettled. In 1565 Suleiman sent an invasion force of about 40,000 men to besiege the 700 knights and 8,000 soldiers and expel them from Malta and gain a new base from which to possibly launch another assault on Europe.[13]

At first the battle went as badly for the Hospitallers as Rhodes had: most of the cities were destroyed and about half the knights killed. On 18 August the position of the besieged was becoming desperate: dwindling daily in numbers, they were becoming too feeble to hold the long line of fortifications. But when his council suggested the abandonment of Vittoriosa and Senglea and withdrawal to Fort St. Angelo, Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette refused.

The Viceroy of Sicily had not sent help; possibly the Viceroys orders from Philip II of Spain were so obscurely worded as to put on his own shoulders the burden of the decision whether to help the Knights at the expense of his own defences.[citation needed] A wrong decision could mean defeat and exposing Sicily and Naples to the Ottomans. He had left his own son with La Valette, so he could hardly be indifferent to the fate of the fortress. Whatever may have been the cause of his delay, the Viceroy hesitated until the battle had almost been decided by the unaided efforts of the Knights, before being forced to move by the indignation of his own officers.

Re-enactment of 16th-century military drills conducted by the Knights. Fort Saint Elmo, Valletta, Malta, 8 May 2005.

On 23 August came yet another grand assault, the last serious effort, as it proved, of the besiegers. It was thrown back with the greatest difficulty, even the wounded taking part in the defence. The plight of the Turkish forces, however, was now desperate. With the exception of Fort St. Elmo, the fortifications were still intact.[15] Working night and day the garrison had repaired the breaches, and the capture of Malta seemed more and more impossible. Many of the Ottoman troops in crowded quarters had fallen ill over the terrible summer months. Ammunition and food were beginning to run short, and the Ottoman troops were becoming increasingly dispirited by the failure of their attacks and their losses. The death on 23 June of skilled commander Dragut, a corsair and admiral of the Ottoman fleet, was a serious blow. The Turkish commanders, Piyale Pasha and Mustafa Pasha, were careless. They had a huge fleet which they used with effect on only one occasion. They neglected their communications with the African coast and made no attempt to watch and intercept Sicilian reinforcements.

On 1 September they made their last effort, but the morale of the Ottoman troops had deteriorated seriously and the attack was feeble, to the great encouragement of the besieged, who now began to see hopes of deliverance. The perplexed and indecisive Ottomans heard of the arrival of Sicilian reinforcements in Mellieħa Bay. Unaware that the force was very small, they broke off the siege and left on 8 September. The Great Siege of Malta may have been the last action in which a force of knights won a decisive victory.[16]

View from Valletta showing Fort Saint Angelo

When the Ottomans departed, the Hospitallers had but 600 men able to bear arms. The most reliable estimate puts the number of the Ottoman army at its height at some 40,000 men, of whom 15,000 eventually returned to Constantinople. The siege is portrayed vividly in the frescoes of Matteo Perez dAleccio in the Hall of St. Michael and St. George, also known as the Throne Room, in the Grand Masters Palace in Valletta; four of the original modellos, painted in oils by Perez dAleccio between 1576 and 1581, can be found in the Cube Room of the Queens House at Greenwich, London. After the siege a new city had to be built: the present capital city of Malta, named Valletta in memory of the Grand Master who had withstood the siege.

In 1607, the Grand Master of the Hospitallers was granted the status of Reichsfürst (Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, even though the Orders territory was always south of the Holy Roman Empire). In 1630, he was awarded ecclesiastic equality with cardinals, and the unique hybrid style His Most Eminent Highness, reflecting both qualities qualifying him as a true Prince of the Church.

5902

VERY Desirable Complete Set with Fascinating Content

The Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Hospitallers, Order of Hospitallers, Knights of Saint John and Order of Saint John, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders during the Middle Ages.

Item number: #5902

Price: $750

Main author: Vertot, abbe de

Title: Histoire des chevaliers hospitaliers de S. Jean de JeÌrusalem, appelez depuis chevaliers de Rhodes et aujourdhui chevaliers de Malthe.

Published: Paris : Quillau, 1737. / complete 5v set

Language: French

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Wear: wear as seen in photos

Binding: tight and secure leather binding

Pages: complete with all 608 + 502 + 563 + 540 + 484 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such

Publisher: Paris : Quillau, 1737.

Size: ~6.75in X 3.75in (17cm x 9.5cm)

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

Shipping:

Very Fast. Very Safe. Free Shipping Worldwide.

Satisfaction Guarantee:

Customer satisfaction is our first priority. Notify us within 7 days of receiving your item and we will offer a full refund guarantee without reservation.

$750

The Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Hospitallers, Order of Hospitallers, Knights of Saint John and Order of Saint John, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders during the Middle Ages.

The Hospitallers probably arose as a group of individuals associated with an Amalfitan hospital in the Muristan district of Jerusalem, which was dedicated to St John the Baptist and founded around 1023 by Blessed Gerard Thom to provide care for poor, sick or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land. (Some scholars, however, consider that the Amalfitan order and Amalfitan hospital were different from Gerards order and its hospital.[1]) After the Latin Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade, the organisation became a religious and military order under its own Papal charter, and it was charged with the care and defence of the Holy Land. Following the conquest of the Holy Land by Islamic forces, the Order operated from Rhodes, over which it was sovereign, and later from Malta where it administered a vassal state under the Spanish viceroy of Sicily.

The Order was weakened in the Reformation, when rich commanderies of the Order in northern Germany and the Netherlands became Protestant (and, largely separated from the Roman Catholic main stem, remain so to this day), and the Order was disestablished in England, Denmark, and elsewhere in northern Europe. The Roman Catholic order was further damaged by Napoleons capture of Malta in 1798 and became dispersed throughout Europe. It regained strength during the early 19th century as it redirected itself toward humanitarian and religious causes. In 1834, the order, by this time known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), acquired new headquarters in Rome where it has remained since. As of 2013, the Roman Catholic order has about 13,500 members, 80,000 volunteers, and 25,000 mostly medical employees,[2] and operates in about 120 countries across the world, including in Muslim nations; the Protestant branches of the order are smaller but engage in similar work. Until recently the order focused mainly on developing countries, but following the introduction of austerity in the Eurozone and the United Kingdom which began in 2010, they have increasingly turned their attention to Europe, establishing shelters and soup kitchens to help the homeless and those suffering from hunger.[3]

Five contemporary, state-recognised chivalric orders which claim modern inheritance of the Hospitaller tradition all assert that The Sovereign Military Order of Malta is the original order and that four non-Catholic orders stem from the same root:[4] Protestant orders exist in Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, and a non-denominational British revival is headquartered in the United Kingdom.

Contents [hide]

1 Foundation and early history

2 Knights of Cyprus and Rhodes

3 Knights of Malta

3.1 The Knights in the 16th and 17th centuries: Reconquista of the Sea

3.2 Life in Malta

3.3 Turmoil in Europe

3.4 The loss of Malta

4 Sovereign Military Order of Malta

5 Protestant continuation in continental Europe

6 Revival in Britain as the Venerable Order of St. John of Jerusalem

7 Mimic orders

8 Remnants

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Foundation and early history[edit]

Grand Master and senior Knights Hospitaller in the 14th century

In 623, Pope Gregory I commissioned the Ravennate Abbot Probus, who was previously Gregorys emissary at the Lombard court, to build a hospital in Jerusalem to treat and care for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land. In 800, Charlemagne, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, enlarged Probus hospital and added a library to it. About 200 years later, in 1005, Caliph Al Hakim destroyed the hospital and three thousand other buildings in Jerusalem. In 1023, merchants from Amalfi and Salerno in Italy were given permission by the Caliph Ali az-Zahir of Egypt to rebuild the hospital in Jerusalem. The hospital, which was built on the site of the monastery of Saint John the Baptist, took in Christian pilgrims travelling to visit the Christian holy sites. It was served by Benedictine monks.

The monastic hospitaller order was founded following the First Crusade by the Blessed Gerard, whose role as founder was confirmed by a Papal bull of Pope Paschal II in 1113.[2] Gerard acquired territory and revenues for his order throughout the Kingdom of Jerusalem and beyond. Under his successor, Raymond du Puy de Provence, the original hospice was expanded to an infirmary[1] near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Initially the group cared for pilgrims in Jerusalem, but the order soon extended to providing pilgrims with an armed escort, which soon grew into a substantial force. Thus the Order of St. John imperceptibly became military without losing its eleemosynary character.[1] The Hospitallers and the Knights Templar became the most formidable military orders in the Holy Land. Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, pledged his protection to the Knights of St. John in a charter of privileges granted in 1185.

The statutes of Roger de Moulins (1187) deal only with the service of the sick; the first mention of military service is in the statutes of the ninth grand master, Afonso of Portugal (about 1200). In the latter a marked distinction is made between secular knights, externs to the order, who served only for a time, and the professed knights, attached to the order by a perpetual vow, and who alone enjoyed the same spiritual privileges as the other religious. The order numbered three distinct classes of membership: the military brothers, the brothers infirmarians, and the brothers chaplains, to whom was entrusted the divine service.[1]

The order came to distinguish itself in battle with the Muslims, its soldiers wearing a black surcoat with a white cross. In 1248 Pope Innocent IV (1243–54), approved a standard military dress for the Hospitallers to be worn in battle. Instead of a closed cape over their armour (which restricted their movements) they should wear a red surcoat with a white cross emblazoned on it.[5]

Many of the more substantial Christian fortifications in the Holy Land were built by the Templars and the Hospitallers. At the height of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Hospitallers held seven great forts and 140 other estates in the area. The two largest of these, their bases of power in the Kingdom and in the Principality of Antioch, were the Krak des Chevaliers and Margat in Syria.[2] The property of the Order was divided into priories, subdivided into bailiwicks, which in turn were divided into commandries.

As early as the late 12th century the order had begun to achieve recognition in the Kingdom of England and Duchy of Normandy. As a result, buildings such as St Johns Jerusalem and the Knights Gate, Quenington in England were built on land donated to the order by local nobility.[6] An Irish house was established at Kilmainham, near Dublin, and the Irish Prior was usually a key figure in Irish public life.

Knights of Cyprus and Rhodes[edit]

Street of Knights in Rhodes

The Knights castle at Rhodes

Further information: Siege of Rhodes (1480) and Siege of Rhodes (1522)

The rising power of Islam eventually expelled the Knights from Jerusalem. After the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291 (Jerusalem itself fell in 1187), the Knights were confined to the County of Tripoli and, when Acre was captured in 1291, the order sought refuge in the Kingdom of Cyprus. Finding themselves becoming enmeshed in Cypriot politics, their Master, Guillaume de Villaret, created a plan of acquiring their own temporal domain, selecting Rhodes to be their new home, part of the Byzantine empire. His successor, Fulkes de Villaret, executed the plan, and on 15 August 1309, after over two years of campaigning, the island of Rhodes surrendered to the knights. They also gained control of a number of neighbouring islands and the Anatolian port of Bodrum and Kastelorizo.

Rhodes and other possessions of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John.

Pope Clement V dissolved the Hospitallers rival order, the Knights Templar, in 1312 with a series of papal bulls, including the Ad providam bull, which turned over much of their property to the Hospitallers. The holdings were organised into eight tongues (one each in Crown of Aragon, Auvergne, Castile, England, France, Germany, Italy, and Provence). Each was administered by a Prior or, if there was more than one priory in the tongue, by a Grand Prior. At Rhodes and later Malta, the resident knights of each tongue were headed by a Bailli. The English Grand Prior at the time was Philip De Thame, who acquired the estates allocated to the English tongue from 1330 to 1358. In 1334, the Knights of Rhodes defeated Andronicus and his Turkish auxiliaries. In the 14th century, there were several other battles in which they fought.[7]

On Rhodes the Hospitallers,[8] by then also referred to as the Knights of Rhodes,[9] were forced to become a more militarised force, fighting especially with the Barbary pirates. They withstood two invasions in the 15th century, one by the Sultan of Egypt in 1444 and another by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in 1480 who, after capturing Constantinople and defeating the Byzantine Empire in 1453, made the Knights a priority target.

In 1494 they created a stronghold on the peninsula of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum). They used pieces of the partially destroyed Mausoleum, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, to strengthen Bodrum Castle.[10]

In 1522, an entirely new sort of force arrived: 400 ships under the command of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent delivered 100,000 men to the island[11] (200,000 in other sources[12]). Against this force the Knights, under Grand Master Philippe Villiers de LIsle-Adam, had about 7,000 men-at-arms and their fortifications. The siege lasted six months, at the end of which the surviving defeated Hospitallers were allowed to withdraw to Sicily. Despite the defeat, both Christians and Muslims seem to have regarded the conduct of Villiers de LIsle-Adam as extremely valiant, and the Grand Master was proclaimed a Defender of the Faith by Pope Adrian VI.

Knights of Malta[edit]

See also: History of Malta under the Order of Saint John

Grand culverin of the Knights Hospitallers, 1500–1510, Rhodes. French work, caliber: 165 mm, length: 540 cm, weight: 3,343 kg, ammunition: 15kg iron ball. Arms of Grand Master Emery dAmboise. Given by Abdülaziz to Napoleon III in 1862.

Arms of the Knights Hospitallers, quartered with those of Pierre dAubusson, on a bombard ordered by the latter. The top inscription further reads: F. PETRUS DAUBUSSON M HOSPITALIS IHER.

After seven years of moving from place to place in Europe the Knights became established in 1530 when Charles I of Spain, as King of Sicily, gave them Malta,[13] Gozo and the North African port of Tripoli in perpetual fiefdom in exchange for an annual fee of a single Maltese falcon (Tribute of the Maltese Falcon), which they were to send on All Souls Day to the Kings representative, the Viceroy of Sicily,[14] (this historical fact was used as the plot hook in Dashiell Hammetts famous book The Maltese Falcon).

The Hospitallers continued their actions against the Muslims and especially the Barbary pirates. Although they had only a few ships they quickly drew the ire of the Ottomans, who were unhappy to see the order resettled. In 1565 Suleiman sent an invasion force of about 40,000 men to besiege the 700 knights and 8,000 soldiers and expel them from Malta and gain a new base from which to possibly launch another assault on Europe.[13]

At first the battle went as badly for the Hospitallers as Rhodes had: most of the cities were destroyed and about half the knights killed. On 18 August the position of the besieged was becoming desperate: dwindling daily in numbers, they were becoming too feeble to hold the long line of fortifications. But when his council suggested the abandonment of Vittoriosa and Senglea and withdrawal to Fort St. Angelo, Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette refused.

The Viceroy of Sicily had not sent help; possibly the Viceroys orders from Philip II of Spain were so obscurely worded as to put on his own shoulders the burden of the decision whether to help the Knights at the expense of his own defences.[citation needed] A wrong decision could mean defeat and exposing Sicily and Naples to the Ottomans. He had left his own son with La Valette, so he could hardly be indifferent to the fate of the fortress. Whatever may have been the cause of his delay, the Viceroy hesitated until the battle had almost been decided by the unaided efforts of the Knights, before being forced to move by the indignation of his own officers.

Re-enactment of 16th-century military drills conducted by the Knights. Fort Saint Elmo, Valletta, Malta, 8 May 2005.

On 23 August came yet another grand assault, the last serious effort, as it proved, of the besiegers. It was thrown back with the greatest difficulty, even the wounded taking part in the defence. The plight of the Turkish forces, however, was now desperate. With the exception of Fort St. Elmo, the fortifications were still intact.[15] Working night and day the garrison had repaired the breaches, and the capture of Malta seemed more and more impossible. Many of the Ottoman troops in crowded quarters had fallen ill over the terrible summer months. Ammunition and food were beginning to run short, and the Ottoman troops were becoming increasingly dispirited by the failure of their attacks and their losses. The death on 23 June of skilled commander Dragut, a corsair and admiral of the Ottoman fleet, was a serious blow. The Turkish commanders, Piyale Pasha and Mustafa Pasha, were careless. They had a huge fleet which they used with effect on only one occasion. They neglected their communications with the African coast and made no attempt to watch and intercept Sicilian reinforcements.

On 1 September they made their last effort, but the morale of the Ottoman troops had deteriorated seriously and the attack was feeble, to the great encouragement of the besieged, who now began to see hopes of deliverance. The perplexed and indecisive Ottomans heard of the arrival of Sicilian reinforcements in Mellieħa Bay. Unaware that the force was very small, they broke off the siege and left on 8 September. The Great Siege of Malta may have been the last action in which a force of knights won a decisive victory.[16]

View from Valletta showing Fort Saint Angelo

When the Ottomans departed, the Hospitallers had but 600 men able to bear arms. The most reliable estimate puts the number of the Ottoman army at its height at some 40,000 men, of whom 15,000 eventually returned to Constantinople. The siege is portrayed vividly in the frescoes of Matteo Perez dAleccio in the Hall of St. Michael and St. George, also known as the Throne Room, in the Grand Masters Palace in Valletta; four of the original modellos, painted in oils by Perez dAleccio between 1576 and 1581, can be found in the Cube Room of the Queens House at Greenwich, London. After the siege a new city had to be built: the present capital city of Malta, named Valletta in memory of the Grand Master who had withstood the siege.

In 1607, the Grand Master of the Hospitallers was granted the status of Reichsfürst (Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, even though the Orders territory was always south of the Holy Roman Empire). In 1630, he was awarded ecclesiastic equality with cardinals, and the unique hybrid style His Most Eminent Highness, reflecting both qualities qualifying him as a true Prince of the Church.

5902

Condition

Excellent

Buyer's Premium

- 0%

1737 History of Knights Templar Hospitaller of Saint J.

Estimate $750 - $1,600

25 bidders are watching this item.

Shipping & Pickup Options

Item located in Columbia, MO, usSee Policy for Shipping

Payment

Accepts seamless payments through LiveAuctioneers

Related Searches

TOP

![1629 HISTORY OF FRANCE ELZEVIER antique Gallia sive de Francorum Regis Dominiis: (Laet, J. de). Gallia, sive de Francorum Regis Dominiis et opibus Commentarius. Leyden, Ex officina Elzeviriana [B. and A. Elzevier], 1629 engraved title, original paperback wrapping, 12mo: 2 1/4 by 4](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/5584/331097/178483610_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1716924779)

![History Indian Tribes of U.S., Reprint Plus Index [182048]: History of the Indian Tribes of the United States, with index: History of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Their Present Condition and Prospects, and a Sketch of Their Ancient Status. Henry Row](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331494/178785298_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717094654)

![Western History Books, 7 [181102]: J Ross Browne's Illustrated Mining Adventures, California & Nevada 1863-1865, Mining Camps by Shinn, Lost Mines of the Old West by Clark, The American West by Brown, Western Memorabilia Collectibles o](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331494/178785574_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717094654)

![Practical Miners Guide, J. Budge, 1845 [181832]: "The Practical Miners Guide" by John Budge, published in 1845 in London for Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, Paternoster-Row. Bound by Westley's & Co. in London. Complete with trigonometrical tabl](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331494/178785610_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717094654)

![J G Bisbee Blacksmiths Archive [181436]: About 8 pieces of ephemera related to J G Bisbee blacksmith including his business card. c. 1867-75. Billheads, indenture etc. Auburn California](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331499/178846605_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717095214)

![Down Memory Trail to The Comstock in Pictures by John J. "Count" Mahoney 1947 [164575]: Down Memory Trail to The Comstock in Pictures - by John J. "Count" Mahoney. No date listed, but its publication is mentioned in the Nevada State Journal on Wednesday, August 6, 1947. An apparently sel](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331499/178846247_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717095214)

![Book Collection: 7 Books by Mary J. Holmes [181724]: (7) Hardcover books by Mary J. Holmes with collectable art on the covers. Homestead on the Hillside; Mildred; Rose Mather; The Rector of St. Marks with DJ; Aikenside with DJ; Maggie Miller; Rosamond.](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331494/178785646_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717094654)

![Montana History Books (4) 1900-71 [182526]: A collection of four books on Montana history, including: 1. "The Vigilantes of Montana, or Popular Justice in the Rocky Mountains," Thomas J. Dimsdale, 1860s original, fourth edition, undated. 290 pp](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331494/178785533_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717094654)

![History of Sierra County, 6 Vols., 1972-82 [182295]: "History of Sierra County," six volumes, includes five volumes of a six volume set, first through third editions, James J. Sinnott, all six author signed, very good. Rare. Numerous historical photos,](https://p1.liveauctioneers.com/2699/331494/178785517_1_x.jpg?height=310&quality=70&version=1717094654)